Back when there was no internet, and therefore no AbeBooks or Amazon or all the other bookselling entities that Jeff Bezos owns, there was Edward R. Hamilton. Hamilton’s catalog showed up in my mail every few weeks. It was tabloid size, thick, maybe 36 or 48 pages, printed on cheap newsprint, unless it was toilet paper. Scores of discount books were crowded on each page, with postage-stamp-sized black-and-white reproductions of the covers and thumbnail descriptions of the contents in microscopic type. The organization was nuts—books were herded into categories, but the categories stopped and restarted in big chunks and tiny bits, seemingly randomly from page to page. I would read it all the way through, looking for the $5.98 and $2.98 deals.

One of the books I saw on offer was a Smithsonian Nature Book by someone named Lawrence Wishner, titled Eastern Chipmunks: Secrets of Their Solitary Lives. I didn’t buy it. Sure, chipmunks were adorable, but would I ever read it? This would have been sometime in the 90s. The years went by. I wrote books, had children, lost my parents, got divorced. Through all that time, Wishner’s subtitle would pop into my head every few days or weeks, like the line of a song I couldn’t stop humming. Secrets of their Solitary Lives. It began to seem like the best subtitle I’d ever heard. Maybe it was the unstated subtitle to all my novels.

In 2012, I began taking notes for a character in a new novel. Mette, 20 years old, would be socially awkward, fiercely private, information-obsessed, somewhere on the spectrum. Although principally interested in math, she would have one area of hoarded knowledge that would seem to come out of the blue, something arcane that dated back to when she was maybe ten or eleven. It would be a secret of her solitary—holy shit.

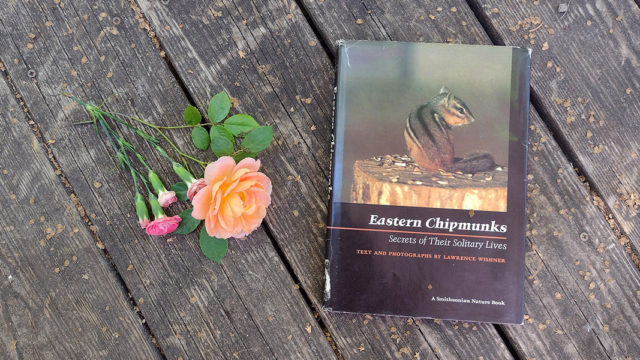

I went on AbeBooks and found it right away. (Isn’t it miraculous how nonliving things don’t die?) It was around $20. I bought it, received it a few days later, read it, and OMG, as young people say (well, they’re probably middle-aged by now)—what a wonderful book! The bio on the back flap said Wishner was a biochemist whose research focused on lipids and the metabolism of vitamin E, but he’d also written on William Butler Yeats and the French physiologist Claude Bernard. Clearly he was a person of wide interests. One of these had centered on the chipmunks who happened to live behind his house. Nearly every day for six years he studied them in his spare time, learned to identify them individually, photographed them, mapped their burrows, dated their hibernations, tracked their family trees. His book is a meticulous examination of their storage habits, mating behavior, vocalizations, social and kinship structure, and more, enlivened here and there with novelistic touches that evoke the chipmunks’ individual personalities. He gave them names like Gutrune, Lady Cheltenham, Pickwick. His photographs are delightful:

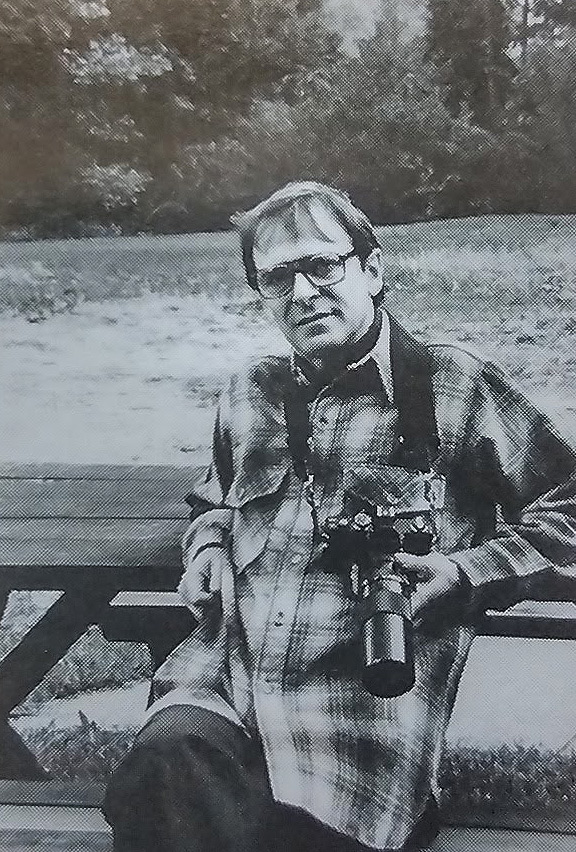

In my novel, Mette loves the book as much as I do. The Latin designation for chipmunks reflects the fact that they are diligent hoarders of seeds: Tamias Striatus, or Striped Steward. Mette dubs Wishner Tamias Tamias Striatus, or Steward of Chipmunks. Perhaps because her own father is absent, she often gazes at Wishner’s author photo.

In May 2006, when she is eleven, she considers writing him a letter, then decides it would be an intrusion on his solitary life. I don’t mention it in the novel, but if she were to change her mind, she doesn’t have much time left. Lawrence Wishner died in October 2006, at the age of 74. His obituary lists some of the other interests he pursued: horses, Islamic art, Gothic cathedrals, roses, geology, sailing, coins, and music.