The first time I saw the City of Tomorrow I was five years old. It was 1965. I had been taken by my parents to the New York World’s Fair. I sat next to my mother in a plastic molded chair on a conveyor belt in GM’s Futurama and watched the City float by like a dream. Its projected date was 2024. It was everything I wanted, but I didn’t know why.

The second time I saw the City of Tomorrow I was ten years old. I must have chattered—I was always a chatterer—to my parents about my hazy five-year-old memories, because for Christmas that year they gave me The World of Tomorrow, by Kenneth K. Goldstein. This 1969 volume in McGraw-Hill’s “International Library” for young readers borrows heavily from GM’s Futurama installation for its photographs and illustrations.

Drinking in the pages, I was stunned that my remembered vision of the City of Tomorrow had not, in fact, been a dream. There it was:

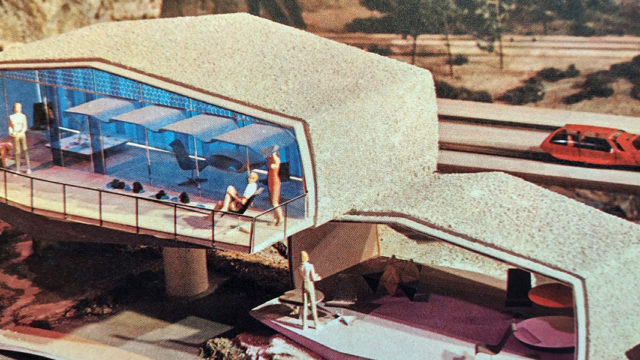

I knew nothing about publishers saving money and labor on illustrations by reprinting previous work, so when I saw the exact same city in Goldstein’s book, I took it as evidence that this was a genuine and ongoing plan. The City of Tomorrow would really be built, and it would look exactly like the photographs. All I had to do was not die before 2024. I would walk in those pristine parks, enter those spic-and-span circular arcades that looked like merry-go-rounds, or Kodak carousels. (No dust to make me sneeze; no messes made by other kids that I would have to clean up.) I would live in one of those buildings with the flared bottoms. Since I had never seen a building with that shape, it was ipso facto futuristic. My future adult self was standing coolly and capably behind one of those bright rectangles of floor-to-ceiling window light. I still couldn’t say why the light entranced me so.

The third time I saw the City of Tomorrow I was fifty-two years old. It was 2012. My mother had just died after a long bout with dementia; my father had died in 2006 after an even longer bout with Parkinson’s Disease. I was about to get a divorce. I was clearing out the old attic, and there the book lay, packed away in a box by my orderly father. It looked exactly as I had remembered it. In my memory, I had read the book “over and over,” as we often say of childhood activities that we did just once or maybe twice. I only remembered small bits of the text.

Vacations are very popular in our World of Tomorrow, for every worker has almost five months off each year. Some people do not work, but prefer to get along on the government’s guaranteed annual income of more than $10,000 a year. [Equivalent to $76,000 today.]

The television sets, as you might guess, are three-dimensional.

The moon is only one of the stations in outer space. Rocket ships accelerating hundreds of thousands of miles an hour have helped develop colonies on Mars and Jupiter as well.

Governments will still be elected, but voting will be much simpler.

Young people will grow up in an atmosphere of security and purpose, for it is likely that the nations of the world will finally be working together to solve their common problems.

Standing in the dusty attic, under the bare lightbulb with the pull string, I stared again at the pictures of the City. They still called to me. My more vivid life, my more deeply felt life, was in that apartment in that building with the flared sides, hidden behind that heavenly rectangle of light. God knows what I did all day. Whatever it was, it was far too wonderful to imagine.

This magical book had the same effect on me, and for some reason, I have never been able to forget it, or locate it. Until now. Thanks for putting this together.