I used to have insane completionist fantasies. At eighteen, when I first entered the stacks of Harvard’s Widener Library, I thought how great it would be to start in the northeast corner of the top floor and read everything until I reached the southwest corner of the basement. Widener Library holds 3.5 million books. Less delusional, but still impractical—considering what a slow reader I am, and how many different subjects are always simultaneously attracting me—when I get interested in a writer, I want to read all their books in the order in which they were written. For example, I would love some day to read Nabokov’s Ada, a favorite of my older daughter, but after reading Lolita, Pale Fire, and Pnin years ago, I became “interested” in Nabokov, which meant I had to start at the beginning. With breaks of months or years between books, during which I’ve continued my glacial progress through other writers’ complete oeuvres, I’ve now read all nine of Nabokov’s Russian novels, but I still have two unread English-language novels between me and Ada. Every now and then my daughter asks me when the hell I’m going to get around to reading this book she’s been urging on me for a decade.

I’m trying to get better. Now that I’m almost 62, I’m beginning to intuit, in a marginally deeper way than previously, that I don’t have enough years left to read all the books currently on my list, to say nothing of the new books that are continually weaseling their way on. A year or so ago I read Susan Choi’s first novel, The Foreign Student, and became “interested.” So I read her second novel, American Woman, and became more interested. I have her third and fourth novels waiting on a shelf, but when her fifth novel, Trust Exercise, won The National Book Award, and a fellow novelist made intriguing comments about it, I took a deep, calming breath and skipped ahead to read it. I’m glad to report that nothing terrible happened. In fact, something good happened: for once, I have an opinion about a novel at approximately the same time most other people do, and therefore could actually have a conversation about literature with other readers at parties, if parties existed today. (My opinion, holding my imaginary glass of wine: Trust Exercise is fantastically good, intelligent and cunningly structured; the best novel I’ve read this year.)

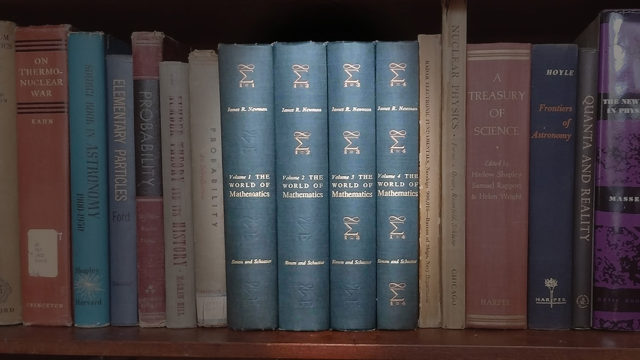

When I was growing up, my father tended to reserve multi-volume sets for a case that stood behind the door of his and my mother’s bedroom: Churchill’s six-volume history of World War II, the three Scribners cinderblocks of C. P. Snow’s Strangers and Brothers sequence, a boxed set of Faulkner’s Snopes Trilogy, and so on. One of the sets was called The World of Mathematics, and when I first noticed it, at maybe age six or seven, I didn’t recognize the symbol stamped in copper on the spine.

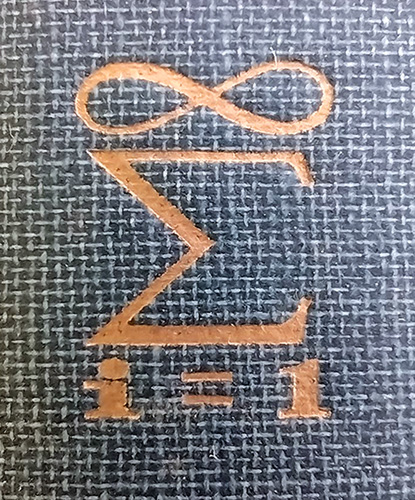

I figured it had something to do with math—duh!—but what it called to my mind, for reasons I couldn’t then and can’t now articulate, was a crowned lion’s head in profile. I never looked into that set, or any of the others—grown-up books were self-evidently for grown-ups—but I liked the pattern the spines made, the lion’s head doubling, then tripling, etc, through the four volumes so that the copper design assembled by the properly shelved books was an inverted right triangle.

In tenth grade I took pre-calculus, and one day, there it was on the blackboard: ∑. My math teacher—a very cool dude with a Miami Vice mustache who drove a Jaguar XKE and later was arrested for dealing cocaine—explained that it was a summation symbol, a shorthand way to indicate a sequence of numbers to be added. The number beneath the figure told you where to start, while the number on top told you where to stop. The indexed variable was often designated i, to stand for “index.” The function to be used was stated to the right of the symbol. For example, if the function was 2i, then each successive number should be doubled before being added; if i 2, then each number should be squared. The figure on the spine of The World of Mathematics, therefore, called for the sum of terms from one to infinity on the first volume, two to infinity on the second, and so on. But since there was nothing to the right of the figure, there was no stated function, which rendered the notation meaningless. This pretty seriously bummed me out. I still didn’t look in the books, or even take them off the shelf. Shit, man, I wasn’t a grown-up yet.

Then I did grow up, but I went to live in a different state. I got married, had kids, visited my parents once each summer and every Christmas. Those four volumes always stood in exactly the same place in the bookcase behind my parents’ bedroom door. In time, my father succumbed to Parkinson’s Disease and died. Then my mother succumbed to dementia and died. It was my job to clear out the house, partly because my brother and sister live much farther away than I do, and partly because I, unlike them, love nothing better than to go through enormous heaps of disorganized and neglected things, so that I can organize them and make them feel less neglected.

So, forty-five years after I’d initially noticed it, I took out and opened the first volume of The World of Mathematics. I read the subtitle: A small library of the literature of mathematics from A’h-mosé the Scribe to Albert Einstein, presented with commentaries and notes by James R. Newman. In that moment, I felt it strongly—the old completionist fantasy. Newman’s four volumes together comprise 2469 pages. How wonderful it would be to start in the upper left corner of the first book and work my way through to the lower right corner of the last book! But now I was old enough—that is, close enough to death—that I accepted I would probably not have the time, given the many other books I wanted to read.

So I did what novelists do with the alternate lives they can’t lead: I foisted the project off on Mette, a character in the novel I was working on, The Stone Loves the World. Mette has plenty of time, because she’s only twelve years old when she starts Newman, and she’s also a true mathematician, not the distractible dabbler that her creator is. So I reaped the novelist’s reward: I read a small fraction of The World of Mathematics, yet came away emotionally convinced that I’d read much more.

Of course I will never read it completely (right? . . . of course not . . . ), but I do intend to dabble in it some more. It’s a great, varied collection, beautifully produced by Simon and Schuster. My copy is 65 years old, yet the pages are unyellowed, the sewn binding tight and supple. When I was a kid, every house that contained any books at all had Churchill’s history of World War II; though Newman was less common, it was a similar prestige set for the professorial crowd, and I saw it enough to make me wonder, in retrospect, how many people owned it without having read it. I wonder what fraction of it my father read. He wasn’t a marker of books, unless he saw a mistake, and he treated his books well, so it’s impossible to know.

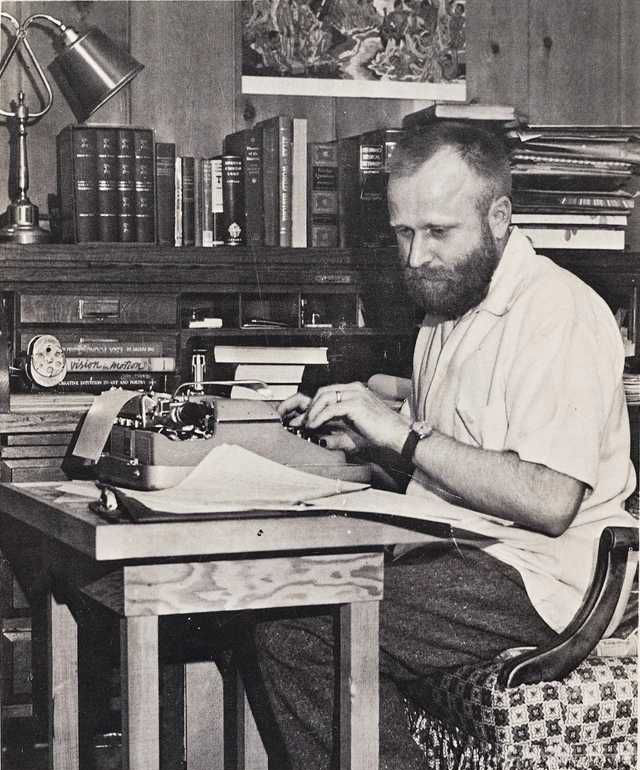

On a side note: science-fiction buffs can wonder how much of it Frank Herbert read. In his author photo for Dune Messiah, which shows him laboring away on the second book in his famous series, you can see Newman’s series under the brass reading lamp on his secretary, looking on.

Note that the volumes are not in order, which suggests Herbert glanced through them at least once. It also suggests that Herbert wasn’t as anal as either my father or me.

Oh, and as for that summation symbol stamped on the binding—it wasn’t until I was an adult that I got the pun. The specific mathematical term for an infinite summation is “series.”