Sure, we had one. My siblings and I got it when I was maybe eight. We had just enough tracks to make an oval with a siding, or a figure eight. We had a New York Central engine and a coal car, a boxcar loaded with finest quality Lehigh portland cement, a tanker carrying hydrocarbon rocket fuel (how cool is that?) and, of course, a red, red caboose.

Being the family nerd and control freak, I was the one who mainly played with it. From plastic model kits I made farm buildings, mills, depots, factories, stations. I didn’t go in much for houses. I couldn’t construct a landscape—I assembled the tracks and dispersed the buildings on the pinewood floor of an upstairs hall and always had to put everything back in boxes when I was done, because of foot traffic. I never made up stories about the workers or the train passengers, I just arranged the buildings in different configurations, then drove my Matchbox cars down the notional streets. (Later, I turned into a novelist attentive to structure and weak on plot.)

When my father first bought the set, as a surprise Christmas gift, he assembled track and train during the night under the tree, so that as soon as we bolted downstairs at 6:00 a.m. we could turn it on and marvel. He’d also completed one HO scale building, which he’d set beside the track. I think this was partly to encourage us (me, mainly) to make more of our own, and partly because he never outgrew a fondness for assembling little gadgets and models. He was a control freak, too.

It’s about the building he made that I mainly want to speak:

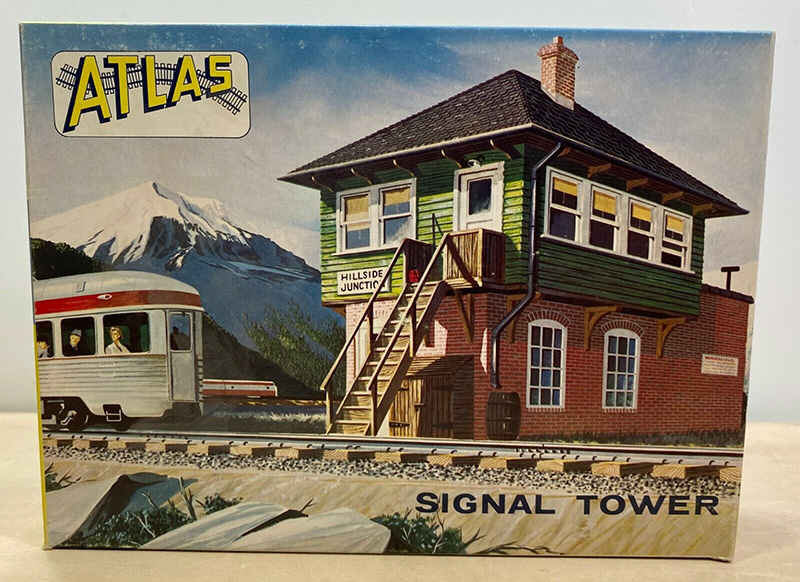

It’s a signal tower, made by the Atlas Model Railroad Company, item #704. Signal towers housed the towermen who operated the levers controlling the semaphores and switch points in the railyard. They worked in the upper room, whose elevation and rows of windows afforded a clear view of the yard. The lower room housed banks of track circuit relays.

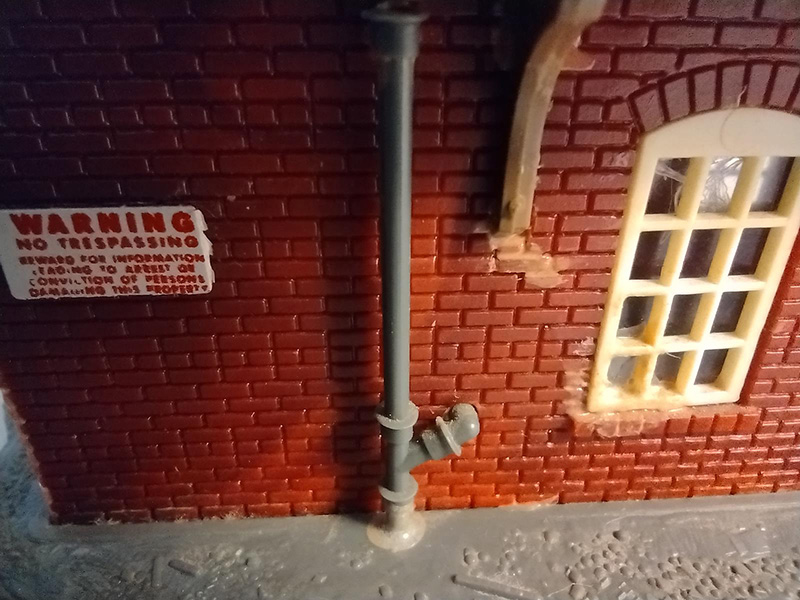

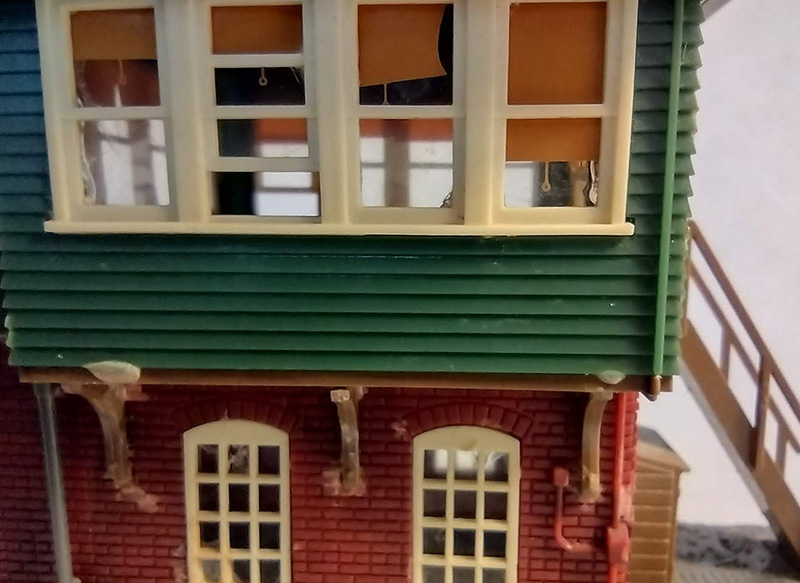

Whenever I set up the track and assorted buildings, I never forgot that the signal tower had been made by my father, who I imagined staying up all night on Christmas Eve, carefully reading the instructions and assembling it while his children slept. My father was not a demonstrative man, so signs of his affection for his children had to be intuited indirectly. It’s no surprise to me now that the signal tower was always my favorite building. I loved the contrasting textures of the brick below and the clapboard above, the contrasting colors of brick red and pine green—Christmas colors. I loved the acetate sheets depicting shades in the upper windows, I loved that you could see the little pull rings, I loved that one of the shades was torn and another one was warped. Talk about verisimilitude! I loved the rounded propane tank by the back door, and the rain barrel underneath the downspout.

I imagined my father up in that signal room, content to be alone behind the “Employees Only” stencil on the glass of the door, putting the trains in proper order like ducks in a row. I was convinced that none of my own buildings had been constructed as neatly as his, although when I compare the models today, if anything, mine look neater.

Hey, that’s what 3 a.m. on December 25th will do to you.

In an earlier post I said that I enjoy examining neglected family objects in order to make them feel less neglected. There’s probably a truer way to put it—by paying attention to an object my father made or preserved (my mother never saved anything), I feel like I’m having a conversation with him that I never was able to have when he was alive. He wasn’t demonstrative, and he wasn’t happy, but he was meticulous and practical. Hey, Dad! Notice how the exterior waste pipe indicates that the toilet is at the rear of the lower floor, behind the circuit relays, so that it won’t stink up the workroom.

And isn’t it smart that the red kerosene lantern is stored outside the upper door, where it presents less of a fire hazard, and yet is ready to hand when the trainman needs it at night to light his way down the steep stairs?

Note how the two windows with raised sashes are on opposite sides of the workroom, providing the cross ventilation that you always fussily insisted on in our house on hot summer days.

My father could easily get obsessed over trivial details, which often enraged my mother. In preparing for this post, I indulged my own inherited obsessiveness (thanks, Dad!). Among other things, I pondered, for the first time, the name of the station: Tamaqua Junction. I googled it, and learned that Tamaqua is real, a town in Pennsylvania coal country where an important railyard was once located. Street-viewing and satellite-viewing, I determined that no switching tower currently exists. I wondered, Why Pennsylvania?, so I looked up the Atlas Train Model company and found to my surprise that it is still in business—somehow I expect all the toy, candy, and mail-order companies of my youth to have been swallowed up long ago by Monsanto—and I saw that you can still buy the exact same model today for $17.95. I street-viewed the modest brick company headquarters and imagined walking in and slapping down a couple of sawbucks for a brand new #704. (Not that I needed one!). The company headquarters are in Hillside, NJ, so the question remained—why Pennsylvania? Well, it was probably Pennsylvania coal in that train engine’s coal car. And the portland cement in the boxcar came from the Lehigh Valley.

Pennsylvania! Player with Railroads and the Nation’s Freight Handler!

I found a photo on eBay of the box the model originally came in, and saw that in the cover illustration the name of the station wasn’t Tamaqua Junction:

Curiouser and curiouser. Eventually I located, also on eBay, an unmade kit for sale, and among the photos depicting the contents there was a blurry shot of the station-name stickers. It turns out there are four choices: Schaffan’s Crossing, Hillside Junction, Schuylkill Junction, and Tamaqua Junction. I knew from the Atlas website that the company had been founded by a Czech immigrant named Stephan Schaffan, so that explained the first name. The location of the company headquarters explained the second. Google maps showed me that Schuylkill was also in Pennsylvania coal country, right next to Tamaqua.

Pennsylvania! Stormy, husky, brawling, State of the Big Shoulders!

I communed more with my father’s shade. Why had he chosen Tamaqua Junction? Did Schaffan’s Crossing not sound railroady enough? Did Hillside Junction sound too generic? Was Schuylkill too hard for an eight-year-old to pronounce? (Maybe he didn’t know how to pronounce it; he had never lived in Pennsylvania.) Then I stopped overthinking it. The stickers go on last; by then, he was probably in a hurry. Tamaqua Junction is at the bottom of the sheet, and when you’re looking at a page of sticky-backed labels, it’s natural to peel away the backing from the bottom corner, where your hands won’t block your view of the printing. He just took the first label he came to.

In contemplating that likelihood—the exact sort of practical explanation for trivial human behavior that my father reveled in—I could imagine him in the room with me. He was unsuccessfully trying to tease apart that finicky corner with his large thumbs, irritated and slightly amused, saying (as he once said to me when he was trying to stand a set of poles in a corner and they kept slipping down), “Brian, don’t you hate it when inanimate objects insist on obeying the laws of physics?”

Hey bro’ – this kind of brought tears to my eyes by the end. I hope you write one about balsa-wood airplane models at some point.

The magic of small details thoughtfully placed; be it the waste pipe on a miniature signal tower or the recognition of your father’s late night efforts to make your christmas morning special. Love the direct path from mindfulness to gratitude drawn by these details.

As for the question “don’t you hate it when inanimate objects insist on obeying the laws of physics?” – my answer is a resounding Yes!