When I was young, my father dutifully paid the family bills in a small enclosed porch opening off the bedroom he shared with my mother in our house in Lexington, Massachusetts. There was just enough room for a secretary, a chair, a narrow bookcase, and two filing cabinets. On the shelves behind the glass doors of the secretary he kept memorabilia: a 1961 Ford Thunderbird he’d made from a plastic model kit and painted cherry-red when my brother and I were toddlers (anticipating, he once told me, the father-son model making to come); a home run baseball he’d got his hands on from inside the scrum when it rolled under the bleacher seats in an Orioles game in the 1950s; a kaleidoscope; a prism; a beautiful old ivory Keuffel & Esser sliderule from his graduate school days; The Bluejacket’s Manual. On the outside of one of the doors, tucked between the glass and a fake mullion, was a photograph taken of him while he was in the U.S. Navy:

I regret the damage, which is all my fault. I’ve loved that photograph ever since I was a small child, and after my father died and I inherited his secretary, I made sure to slip the picture into its old place, by way of a memorial. But I neglected to consider that the room in which I keep the secretary, unlike my father’s old cubby-hole, gets a lot of direct sunlight.

I don’t have many photographs of my father. His family was poorer than my mother’s, less educated. His own father, Jonathan Heggie Hall, known all his life as J.H., was born in 1883 in the Appalachian hills of western North Carolina—specifically, Wilkes County, which later, during Prohibition, became known as Moonshine Capital of the World. I’ve only ever seen one image of J.H.’s family, a photograph of a photograph:

J.H. is the boy on the left, with his hand held stiffly horizontal. Years later he told my father that he’d never before had his picture taken, and he had the notion that this was the pose a man should strike for a photographer. I’ve seen his middle name spelled variously as Heggie, Hegge, and Heggy. J.H. himself didn’t know how to spell it, because he had never seen it written.

Neither of my parents talked much about their origins; everything I know about this hill family I can say in one paragraph. Sometime after this photo was taken they moved downstate to Gastonia, to work in a cotton mill. Later, J.H.’s father (back row, left), sold patent medicines. Buren, the boy standing next to J.H, died in his early twenties when he climbed an electric pylon while out hunting and got himself electrocuted. J.H. escaped the cotton mill by landing a job with the Durham Life Insurance Company. He finagled a position in the same outfit for his youngest brother, James Thomas, or J.T., (front row, right) and years later J.T. averred that, by doing so, J.H. had saved his life.

When J.H. was 39 he met Edna Eula Hudson, a fellow North Carolinian who, at 29, had never been on a date and had never been alone, as she was raised to be the constant companion of a developmentally disabled older sister. The death of this sister had released her. J.H. and Edna married in 1923. Edna suffered from anxiety and, later in life, autophobia. J.H. was a sales agent for Durham Life in Durham, NC, eventually rising to a position as district manager for the company in Wilmington, NC, but the couple never had much money. At one point there was a sizable loan to a friend that was never repaid. They had three children, the second of whom, born in Durham in 1926, was my father, Louis Alton Hall.

Alton, as he was called, was a prodigy in school. I’ve seen all his report cards, going back to elementary school—his proud mother saved them—and there are nothing but As in every subject, every quarter, every year. I mean, there are no A minuses. That kind of early and purportedly objective validation can make a person intellectually arrogant. Later in life my father would say regretfully that his older sister and his mother were dumb, while his younger brother was not nearly as talented as he thought he was. The only person in the family he respected—or even liked—was J.H., who died of a heart attack when Alton was 32. After that, he had only sporadic contact with his mother and siblings.

Finding academics so easy, he had plenty of time for other activities. In high school, in Wilmington, he was Sergeant-at-Arms in the student legislature (his schoolwide nickname was “Muscles”), Chief Judge of the Student Court, and Treasurer for the National Honor Society; he sang in the Glee Club and took the role of the Boatswain in the school operetta, HMS Pinafore; he played saxophone in the ROTC band and a jazz ensemble at school dances. He graduated—valedictorian, of course—in June 1944. (He never told me any of this; I’ve gleaned it from his high school yearbook, which he never showed me, but characteristically saved in a box in the attic.)

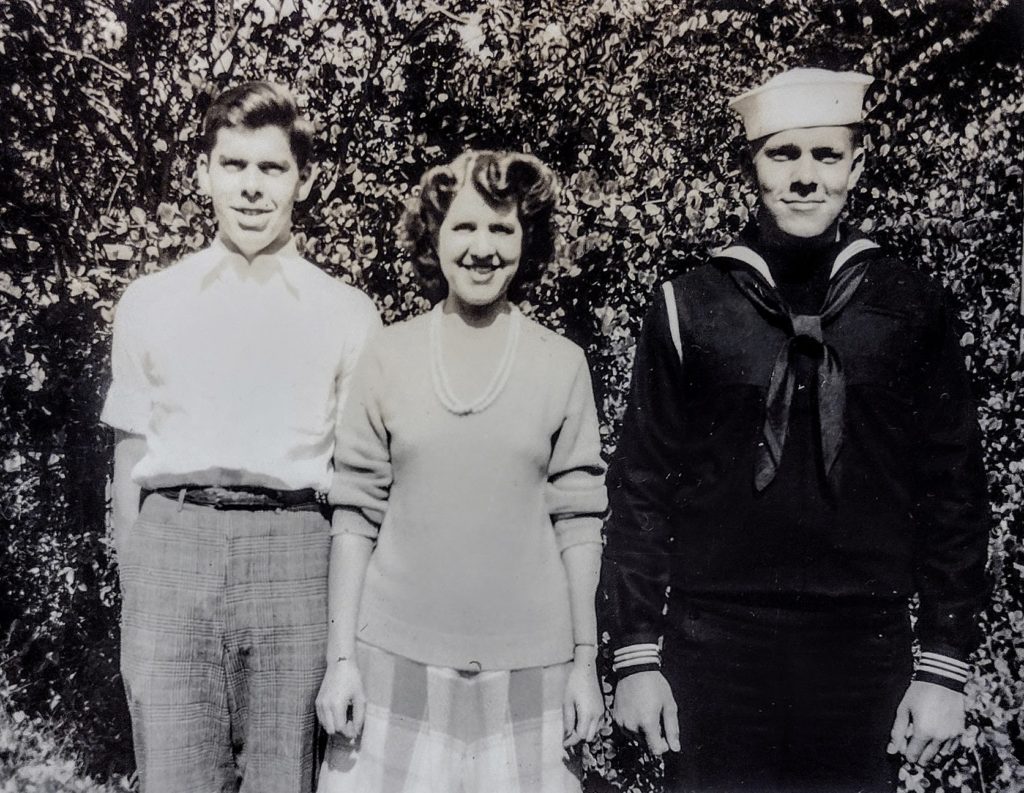

He had already registered with the draft board, and because of his math and science skills he was encouraged to take the Eddy Test, which was administered by the U.S. Navy during World War II to locate prospective radio and radar technicians. He passed (of course!), and was inducted into the Navy on July 29, 1944. Here he is, eighteen years old, just before heading off to boot camp at Great Lakes, Illinois, along with his younger brother, Furman, and his older sister, Ruth:

Here he is again, a year later and twenty pounds lighter (his arms seem to have grown longer, too):

The course of instruction in radio and radar—a new technology desperately in need of technicians—was long. After six weeks of boot camp, there were four weeks of pre-radio school, twelve weeks of primary instruction, and twenty-seven weeks of secondary. If everything had proceeded on schedule, my father would have completed his training in early July 1945 and probably been shipped out to the Pacific theater for the last month of the war. This is what happened to a number of his classmates. But during his primary training, in Gulfport, Mississippi, he was injured in one hand by high voltage electricity—maybe it was a family curse—during a machine repair speed trial. He spent three months in the hospital. He later said that his hand healed in half that time, but the Navy took the usual dog’s age in assigning him to a new unit. Consequently, he was still in the secondary radio program, at Navy Pier in Chicago, when the war came to an end. He completed his service without leaving the city, and was discharged in July 1946.

Which brings me back to the photo I knew and loved as a child:

It was taken by a street photographer. My father explained to eight-year-old me that in those days someone might snap a candid shot of you on the street, then hand you a card with the address of the studio they worked for. You could come by later to look at the photograph, and if you liked it, you could buy it. This photo was presumably taken in late October or early November 1945, because the movie Johnny Angel was released on October 25, and the full superscript on the marquee probably reads something like “First Chicago Showing.”

Why did I like it so much? For one thing, I liked the story about the street photographer. Those strange customs of the distant past! More importantly, it was the only photo I’d ever seen of my father as a young man. (His few other photos were not in albums, but hidden away in boxes up in the attic.) And I was fascinated to see my father in uniform, because he was so vocally anti-military. The only times he ever acknowledged his stint in the Navy—other than when he needed to explain the heavy scarring on three of his right-hand fingers—were when he sang the bugle’s Mess Call with the words about the soup not having any beans or, on very rare occasions, when I or my siblings begged for it before bedtime, “Asleep in the Deep,” thrilling his alto-voiced pre-teen son with the slide at the end, on the word “beware,” down to the low D. He had a good ear, and a fine, mellow bass-baritone voice.

He explained that, when the photo was taken, he was counting change in his palm. I don’t think he ever said what he was planning to spend the money on, but I’ve always imagined it was music—a score, a recording, a performance nearby. Maybe he was about to turn around and buy a ticket for Johnny Angel, just so he could hear the associated short, Louis Jordan’s Hep-Cat Serenade. He’d been a jazz aficionado in high school, during which he’d spent some of his earnings from his summer and weekend job at a men’s clothing store to buy shellac 78s featuring Duke Ellington, Lionel Hampton, Benny Goodman, Harry James, Red Nichols, etc. (By now, you can guess: he never told me, but he saved all his records.)

He continued to listen to jazz at Wake Forest College, which he entered after his Navy service in the fall of 1946, but he no longer played or sang in any ensembles. Post-war, it seems it was time to get serious: he joined the Physics Club and the Math Club, and was elected president of the Baptist Student Union. In his senior year he got engaged to a woman. I only heard about her existence from my mother, who didn’t tell me her name, and perhaps had forgotten it. But since my father saved even his old pocket memorandum books, I found in one of them a crossed-out reference to a Phoebe and a ring, and with the aid of his yearbooks and some internet searching, I learned that this Phoebe was a fellow senior, a Religious Education major who was also in the Baptist Student Union. In October 1949, Alton and Phoebe were one of the “sponsoring couples” for Wake Forest’s Homecoming football game against William and Mary, and four days later they got engaged. My father apparently didn’t have enough money at the time for a ring, because he didn’t buy one until the following April. I presume he once had a number of photographs of Phoebe, but he must have destroyed them; or maybe my mother did. Only one has survived:

I have no idea who the clowning fellow in the middle is.

I mention Phoebe, because she was possibly the principal cause of my father and mother getting together. I had always longed to discover some explanation for their spectacular mismatch. When my father moved to Baltimore to start graduate studies in physics at Johns Hopkins in the fall of 1950, Phoebe remained in North Carolina. My mother was another first-year physics graduate student at Johns Hopkins, and she was acquainted with my father through shared classes. At some point toward the end of the first semester, Phoebe mailed back to Alton her engagement ring. My mother only ever said two things about it, the first being, “He was really broken up about it; I felt kind of sorry for him.” The second was prompted when I asked her if she knew why Phoebe had ended things: “She probably figured out what he was really like.”

I’ve said that my father was intellectually arrogant, and my mother hated male arrogance. He was authoritative, and she hated all authority. She’d grown up an only child, disliking her parents and longing for a younger sibling. The only tenderness she ever expressed was for the vulnerable creatures who needed her authority, who cared about her good opinion: her children and her pets. My father never showed vulnerability and was always perfectly satisfied with his own opinions—that is, until my mother moved out of their shared bedroom, when I was in my twenties. He was really broken up about that. He seemed, in fact, shattered by grief. He hated to cry in front of his children, but he would occasionally break down (if my mother wasn’t around), at which point he would always say the same thing: “I feel as though I’ve lost my sweetheart.” I suspect that what I saw at these wrenching times was something similar to the temporarily self-doubting and endearing man that my mother had seen when Phoebe broke up with him. Another notation in that old memorandum book, written immediately below the crossed-out reference to Phoebe, records the date of my parents’ first kiss: January 25, 1951. This was only a few weeks after the broken engagement. In June 1951, another ring was purchased; or perhaps it was the same ring. My parents were married in December 1951.

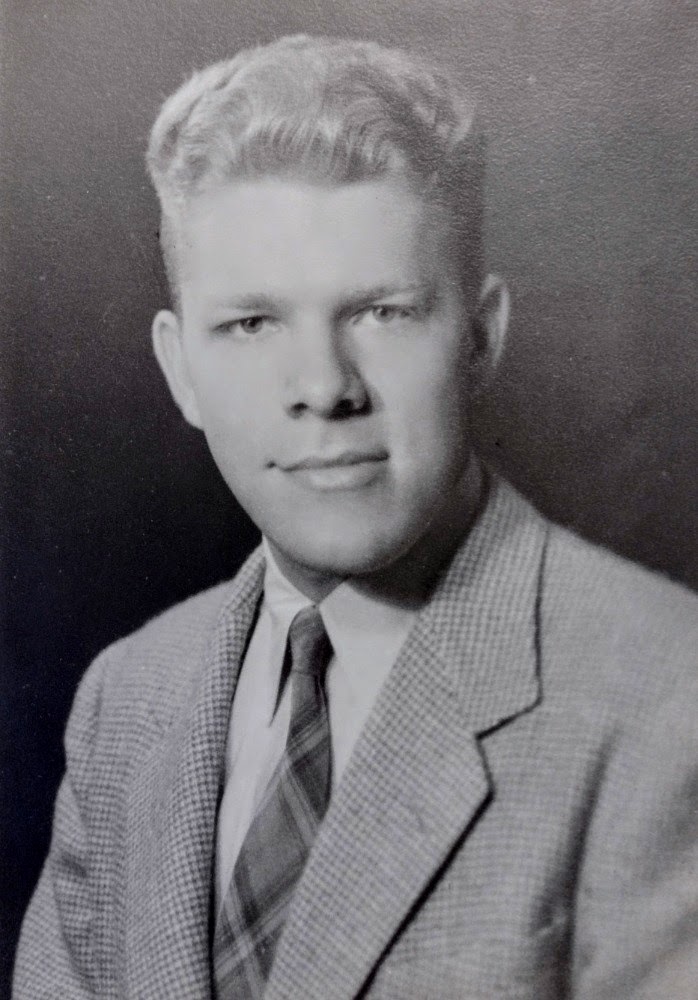

Here’s a photograph of my father in his early twenties:

And here he is, forty-five years later:

Is it only to my eyes, or would his unhappiness in the second photograph be evident to any viewer? The cause wasn’t solely his relationship with my mother. For years he had felt restless and somewhat bored with his work as a solar physicist. Also, at the age of 58, he had begun showing symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease. But he always said the same thing to me about the root cause of his unhappiness: “I can date it exactly. But it would be unethical to speak about it to my children.” By refusing to reveal it, he made it obvious.

It has probably become clear by now that if my parents ever said anything about their relationship—any reluctant, terse, dismissive, deflecting thing—then if they repeated it later, they did so verbatim. The last twenty years of their relationship seemed hopeless because it was locked inside these never-changing formulations.

My father’s consolation was classical music. Ironically, it was my mother who had introduced him to it. She had grown up playing classical piano, winning certificates and awards in recitals, going to hear Horowitz and Rubinstein in concert. Contrarian by nature, she had rejected her Southern Baptist background by becoming a high church Episcopalian, and through the force of her ironclad opinions, she dragged the former sax-playing Baptist Student Union president with her. They were married in an Episcopalian church near where my mother grew up, and in Baltimore they attended services at the Episcopal Cathedral of the Incarnation, half a mile from their apartment. It was in these high church services that my father first heard Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mendelssohn. He never looked back.

His new interest in classical music was perhaps a form of allegiance to his new wife, and a step away from the unlettered family he was half ashamed of. Just weeks after his wedding, he bought his first labels through a subscription service advertised in the Schwann Catalog, 10-inch vinyl 33rpms packaged by the Musical Masterworks Society, featuring titles such as the New World Symphony, the Peer Gynt Suite, the 1812 Overture, Night on Bald Mountain. There was also some Beethoven:

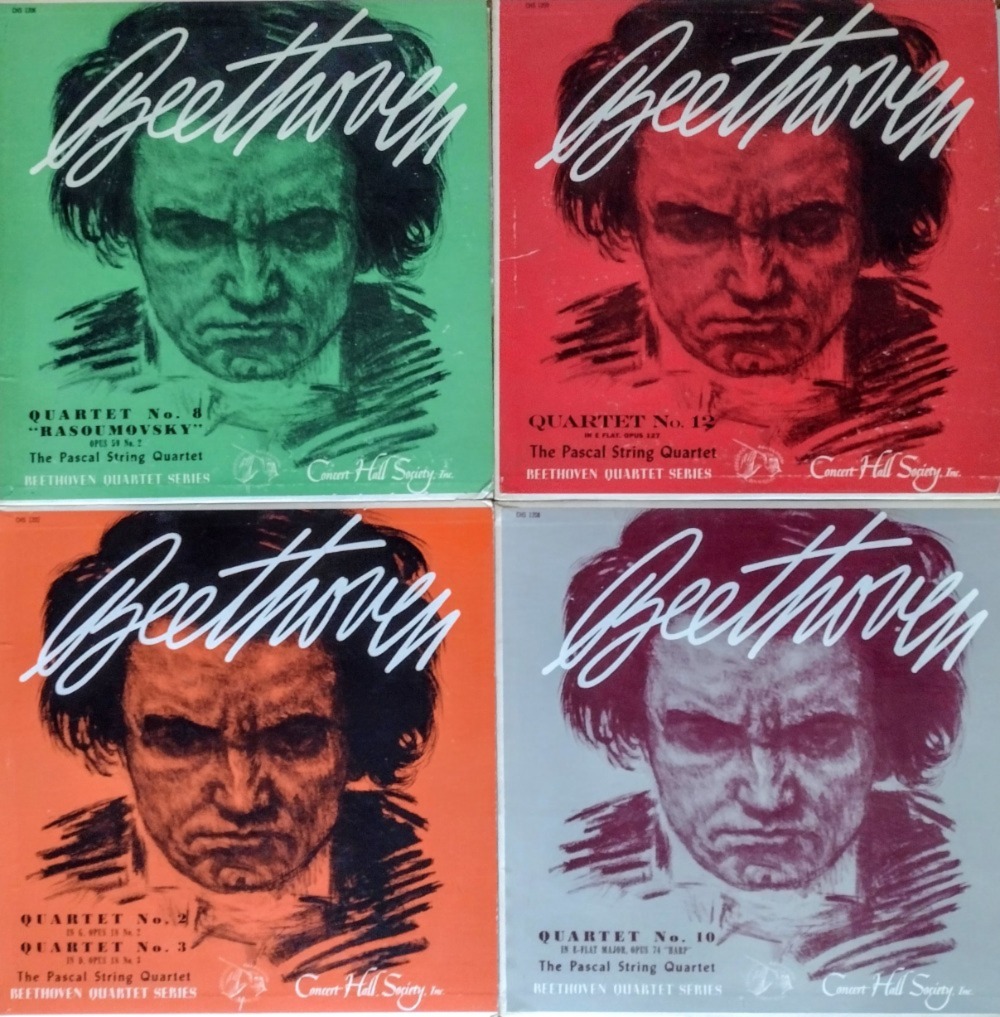

When my father switched to 12-inch records in 1953, his very first purchase was a set of the Beethoven string quartets, issued by the same company under the Concert Hall Society label. Years later, beginning when I was maybe six or seven, I would occasionally catch sight of the uniform, color-coded covers of these old recordings, moved to this or that new shelf by my father as his LP collection grew. A timid kid, I was alarmed by the Bad Dad sketched in heavy charcoal, which remains, fifty-five years later, my instinctive mental image of Beethoven.

Neither of my parents were playful, but when my brother and I were young, my father dutifully engaged in a few activities with us—my sister, being a girl, was left out—that were patterned after the childhood games he had played with his own loved and much missed father: catch, three-person touch football, balsa wood airplane model making. All the rest of his free time was spent either tinkering at his workbench in the basement—he could fix anything in the house—or sitting at the dining room table (we always ate in the kitchen) with his headphones on, listening to music. As my brother and I grew older, the games naturally faded away, and in my adolescence most of my interactions with my father would occur when he caught sight of me coming through the dining room and would take off his headphones, pull out the jack to activate the speakers, and say, “Brian, listen to this.”

He was an adventuresome consumer. He learned to appreciate Bartók, Poulenc, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, Hindemith, Ives, Martinu; he tried, and kept trying all his life, to appreciate Schönberg, Webern, Carter, Babbitt, Ligeti, Penderecki, Messiaen, Cage. (My mother, on the other hand, declared that listenable music had ended with Brahms.) Saying, “Brian, listen to this,” he once introduced me to Steve Reich’s Four Organs, and I, the supposedly open-minded young musician, was the one who recoiled in disgust, rejecting it out of hand, while my father chuckled and said he didn’t get it, either, but wasn’t it kind of interesting? His attitude toward music was that of a scientist studying a phenomenon that was often beautiful, occasionally baffling, always fascinating. Unlike the vast majority of snooty classical music aficionados—and unlike me at age fifteen—he wasn’t frightened by experimentation; it merely prompted him to continue his own experimental listening.

He always claimed he had no musical talent of his own, insisting that he’d been a terrible saxophone player. If he undervalued himself, he tended to overvalue my abilities as pianist and bassoonist. I’m pretty sure he hoped I would have a career in music, but didn’t want to burden me by saying so. He hated to travel, but he flew with me to Oberlin College when I was considering a double major there in bassoon performance and physics. He attended every concert I ever played in, all the way through my college years (which were not, alas for him, at Oberlin), appearing in the warm-up room after each performance and drawing my attention with the same half-abashed cheer: “Yay, bassoon!”

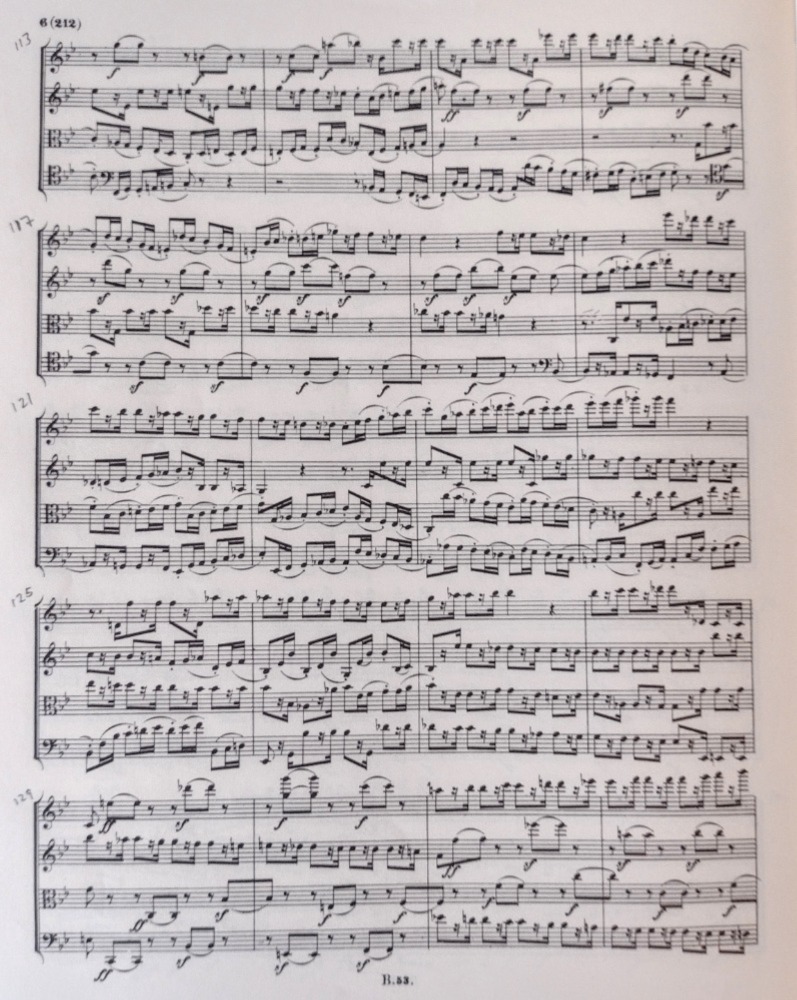

As the years went by, as his children moved out of the house and his relationship with our mother worsened—she, bitterly angry at him and he, infuriatingly clueless as to why she was so angry—he devoted more and more of his free time and intellectual energy to music. He was fascinated by Charles Ives’ and John Cage’s experiments with music-as-soundscape and soundscape-as-music. He explored the various frequencies of the glassware in the house. He brought home from his lab a superannuated oscilloscope and investigated the wave forms of musical instruments, including his own voice. He bought and read analytical books such as The Beethoven Companion, Joseph Haydn and the String Quartet, The String Quartet: A History, The House of Music, and Introduction to Contemporary Music. He read biographies of Bach, Ives, Bartók, Shostakovich, and Beethoven. He read the memoirs of Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and the Guarneri Quartet. He read with particular fascination the novelist Anthony Burgess’s account of his shadow life as a composer, This Man and Music. He owned A Dictionary of Musical Themes, Lectionary of Music, and the Harvard Dictionary of Music. He chortled through the Lexicon of Musical Invective: Critical Assaults on Composers Since Beethoven’s Time. He purchased and personally beat up Dover scores for the complete chamber music of Beethoven, Schubert, Mozart, and Brahms, plus the two-volume The Norton Scores: An Anthology for Listening. He hadn’t been able to find for sale, and so instead xeroxed and bound a library copy of Deryck Cooke’s analysis of Wagnerian leitmotif, An Introduction to Der Ring des Nibelungen. He learned the antique church modes. He jotted down calculations based on the simple fractions governing the frequencies of consonant intervals. He bought himself a cheap classical guitar and a primer and laboriously, over several years, taught himself to play three or four of the simpler canonical pieces.

He never returned seriously to the saxophone, probably because it’s not suited to most classical music, but one Thanksgiving, for some unstated reason, he assembled his old instrument and honked through a couple of tunes, decrying his tone and his clumsiness, while I took a rare photograph. Portrait of the jazz man at 64:

He continued to listen at the dining room table, now dutifully paying the household bills there, his turntable and two tape decks within easy reach behind him. Wearing his large headphones, his gaze abstracted, he looked like a floating astronaut, or a creature in an aquarium. He was content to be closed off from the world—as content, anyway, as he was capable of being. When I devised a fictional version of him I gave him a fallout shelter underneath the house in which to listen. He told me once, late in life, that he missed terribly the days when his children were small—a more bearable way, I think, for him to recall a time when my mother could stand him—and the instance he gave of a memory that haunted him was illuminating. It wasn’t about playing some game with us, or holding us, or listening to us. It was about sitting at the dining room table, enclosed in his headphones, gazing through the open door into the living room and watching us play, curious about what we were doing, but not enough to turn off the music and find out.

In his last years, filled with emotions he didn’t know how to articulate, nor trusting the communicability of even the best words, my father saw music as representing a purer vehicle of human sentiment. And like many lovers of classical music in their unhappy declining years, he considered the Beethoven late string quartets to be the supreme example of transcendent human expression rising out of, and in spite of, illness and heartbreak. By then, he owned nine complete vinyl recordings of the late quartets and had taped radio performances of a dozen more. “Brian, listen to this”—when I visited, he would pause a performance and play me a passage, often ask me a technical question about a key change, a chord progression, a transfigured motif, as though I knew more about the quartets than he did, when in fact I knew less.

In his scientific work, my father was a talented instrument designer and calibrator, and when he increasingly told me that he wanted to “understand” the music that moved him so powerfully, I think he meant that he longed for better insight into the technical means by which a piece of music aroused certain emotions. Among the various thorny movements of the late Beethoven quartets, the one that stood out for him in this regard was naturally the Grosse Fuge, which flummoxed Beethoven’s contemporaries and even today overwhelms most listeners. It certainly overwhelmed my father, no matter how many times he played it. As it happens, it was the last piece he ever stopped me for, pulling out the jack and resetting the needle at the beginning. He was probably around 75; I would have been 42. As the juddering lines of the ridiculously complicated fugue careened around the dining room, he uttered one last time the self-judgment to which he’d become resigned and which, in an odd way, seemed now to comfort him: “I will never understand it.” Despite his now-advanced Parkinsonism and his chronic depression, the near-cacophony clearly exhilarated him.

My father’s final five years were very hard. As it will do, Parkinsons patiently and tirelessly took everything from him, one piece at a time. My mother took good physical care of him, but showed him no affection, at least in my presence. He became wheelchair-bound, suffered Lewy body dementia, and spent his last year in a nursing home, expressing the wish to die. When he stopped eating and drinking, I and my siblings were called in from Ithaca, St. Paul, and Santa Cruz. My brother was still in the air when my sister and I reached him. It wasn’t clear that he knew we were there, but we held his hand and told him that, despite whatever our mother said, he’d been a good father. My sister sang sotto voce for him an aria she used to practice, years ago, in the dining room, with me accompanying her on the family upright. Before starting another, she and I chatted by his bedside, catching up on minor news, and during those minutes, he died.

For me, the Grosse Fuge “makes sense”—if one feels a need to explain its uncanny power—as an expression of the untameable unruliness of the phenomenal world, its ultimate inexplicability; what Robert Frost in a letter called the “things that suggest formulae that won’t formulate—that almost but don’t quite formulate.” This was where Frost said all the “fun” was. He was being unbuttoned, so he didn’t say it was where all great art lies. The efforts of a human being—of a composer, say, employing a highly formal art like the fugue—to rein that chaos in, to order it, is valiant, but will always be insufficient. The Grosse Fuge is “incomprehensible” because it dares to evoke life’s incomprehensibility.

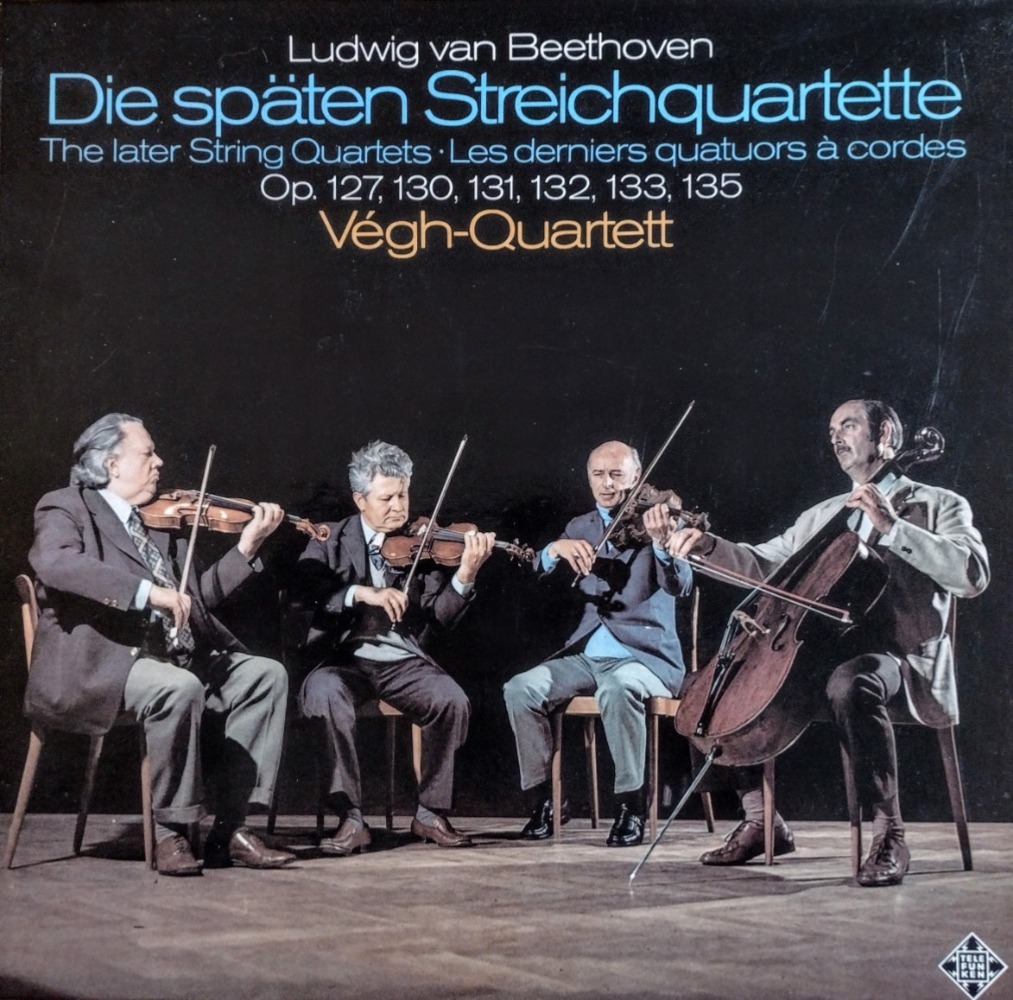

I was the only child who lived close enough to the old family home to make renting a truck feasible, so after my mother died, my siblings allowed me to take the bulk of my father’s LP collection, numbering about 3500 disks. While stuffing them into every spare shelf, nook, and cranny of my study, I paused over a lot of familiar covers, including one depicting the Végh Quartet on their set of the late Beethovens. I had often glimpsed this photograph at my father’s elbow, because the Végh’s renditions were among his favorites—subtle, solid, unfussy, unshowy.

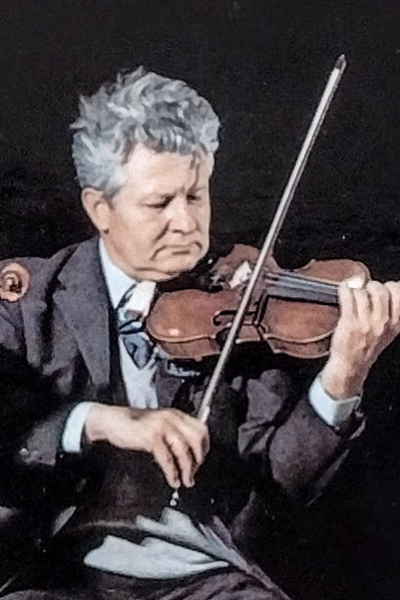

If, as I’ve written elsewhere, my mother led a happier life in an alternate universe as an equestrian not married to my father, then my father surely led one as a string quartet player not married to my mother. For years I wished on him the quantum-mechanical, many-worlds magic that would have allowed him to be, say, a second violinist in a fine ensemble closely resembling the Végh. That less conspicuous and supporting role seemed fitting for a man who who was always too modest about his musical talents, and who preferred to keep himself somewhat hidden.

Abracadabra!

Brian, I love the photograph you call “portrait of the jazz-man.” It forms such a great counterpoint to the earlier photo where his mouth seems set so grimly (or is it the Parkinson’s?) Here I see again his open-eyed curiosity (or is he looking up at you as you take the photo?) and I see the capacity for ebullience that he never totally lost until the very bitter end (or is it just the effort of blowing through the saxophone?) I feel strangely happy knowing I will never know the answers to these questions. Like all human beings, perhaps especially perplexed and unhappy ones, Dad will always remain a mystery in so many ways.