On September 3, 1976—the day Viking 2 touched down successfully on the surface of Mars—I bellied up to a registration table in a hotel in Kansas City, Missouri, to receive my name tag and program book for MidAmeriCon, the 34th World Science Fiction Convention. I was seventeen years old. Other than Jennifer Vozoff, with whom I had held hands on the school bus three days running when I was in third grade, I had not yet had a girlfriend.

I was a devoted reader of science fiction, but I had never been to a science fiction convention. Standing outside the Imperial Ballroom, waiting to get into the Opening Ceremonies, I looked around at the attendees, mostly male, and thought, What a bunch of unattractive geeks and social outcasts. (I would discover later that many male science fiction fans think this when first encountering other male science fiction fans.) The fellow I mainly recall had the signature unwashed, scraggly hair and was playing parodic tunes of his own invention on a portable keyboard powered by his breath. Whenever he removed the flexible hose from his mouth, a quarter cup of saliva would dribble over the mouthpiece. He called himself Filthy Pierre.

On that first day, I attended a panel titled “SF, Why Bother With this Crud?” and was kinda bored. Afterward, there was a fanzine seminar, but I had no idea what a fanzine was, so I didn’t go. There was another panel, “Women in SF,” but I’d never heard of any women in SF except for Ursula K. Le Guin, and she wasn’t there, so I didn’t go. I went to “Life in Outer Space,” and found it less boring than the first panel, but still pretty boring. In the hallways I glimpsed a couple of wary authors and realized that I didn’t care about meeting any authors. That night I went to see the Dramatic Production, Sails of Moonlight, Eyes of Dusk, in the Municipal Auditorium and fell asleep somewhere during the third of four hours. All I can summon up now is a stage set of Stonehenge-like monoliths and a procession of tunic-wearing actors declaiming lines with their feet planted too far apart.

I had arrived on a Greyhound bus from Washington, DC, with my best friend from music camp, Larry. We couldn’t afford a room in the convention hotel, so we stayed at the YMCA a few blocks away. The cockroaches waving their feelers at us in friendly fashion from the stained wallpaper were a novelty to me, but Larry, who’d grown up in the Bronx, threw his shoes at them like a pro. Larry was even more of a devoted science fiction reader than I was, but toward the end of that first day both of us were unsure what we’d come all this way for. Then we discovered the film program, which ran from 11 AM to 3 AM every day. Although VCRs existed in 1976, nobody owned one because they cost $1300. It would be twenty more years before the term “binge-watching” was invented, but Larry and I didn’t need no stinking term for it. It had never occurred to us that anywhere on the planet there might be such a thing as a near-endless procession of sci-fi movies available to hoover like hotdogs at a Nathan’s contest. We planted our soon-to-be-numb butts down in the metal fold-out chairs in the Grand Ballroom and didn’t budge for three days.

Well, we did walk back to the Y in the early morning hours. We bought sandwiches and soggy burgers from a vending machine in the lobby, our only food for the day. There was also a microwave, but neither of us had operated one before, and we were both a little scared of it. We would hit the power button and back up ten feet. I can’t remember if we shielded our gonads or not.

Another term that had not yet been invented was “incel,” but by the strict definition of that term, I was one: I very much wanted a girlfriend, but had no idea how to get one. Since I wasn’t brave enough to ask a girl out, the only course of action seemed to be to wait for a girl to ask me. But in 1976, outside of a Sadie Hawkins dance at which I was the only male, this was unlikely to happen.

1976! Year of the Viking landings and the Bicentennial! Year in which Jimmy Carter promised never to lie to us! The National Organization for Women had been founded ten years previously, but what strikes me now, looking back at MidAmeriCon, is how very little progress had yet been made in altering males’ attitudes, including mine, toward females. Science fiction is an especially good indicator of cultural biases and blindspots, because it’s supposed to be all about imagining alternatives, so the things in science fiction that never change are the things that writers and readers literally cannot see.

In this context, I mean male writers and male readers. That panel I skipped, “Women in SF,” was the first of its kind at any science fiction convention, and it was the only panel that was scheduled in conflict with something else. I’ve kept the MidAmeriCon program book, which lists the names of all the people who pre-registered for the convention in the order in which they did so, so it’s easy to calculate that 72% of them were male, 28% female. Of the women, 40% share the last name of the man listed immediately before them, which suggests they were wives following their husbands. Thus, only 17% of the attendees—this would be at most, since I can’t account for couples with different last names—were women choosing to come on their own.

Here’s the cover of that program book, which was handed to everyone on the first day along with their name tag:

The artwork is by the well-known sci-fi and fantasy artist George Barr, who explains on the program’s back flap, “The boy is not a sophisticated seventies teenager . . . The visions he sees are those depicted on so many of the covers of the magazines of twenty or thirty years ago: the heroic captain, the lovely and virginal alien princess. . .” The captain has been given the face of that year’s guest of honor, the 69-year-old Robert A. Heinlein, which might or might not be sufficient to explain the yawning age gap between the hero and his reward. The princess, in any case, must be both virginal and nubile. The hero, like a bumblebee, or a manorial lord enjoying droit du seigneur, must be allowed first crack (so to speak) at the prize so that he can symbolically, or maybe really—who knows how this alien princess’s biology works?—father all of her subsequent progeny. Two interesting details to note: the princess’s bikini bottom is decorated with a helpful “o” to mark the spot; and although we can’t see what the hero is doing with his right hand, he has removed his glove in order to do it. Of course the pictured reader is a boy, rather than a girl.

The program book is 167 pages long. (Geeks love to geeksplain.) It includes commentary, introductions to the featured guests, reminiscences of past conventions, two short stories, advertisements, and a list of the scheduled movies. The announcement that the 38th World Science Fiction Convention will be held in Boston appears on page 70:

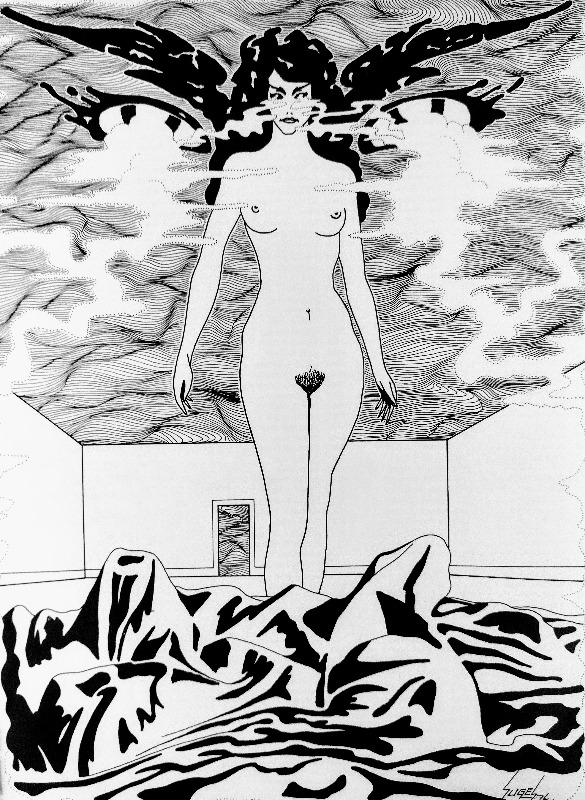

I sense a theme. Men are men, and women are . . . what, exactly? Outlandish; other; not really human. For those who like this sort of thing, there’s a further variation on page 112—this is the illustration for Harlan Ellison’s short story, “Lonely Women Are the Vessels of Time”:

In 1976—I will not lie to you—I probably noticed none of this. I hardly remember the program book at all. What I remember are the movies, most of which I was seeing for the first time: Forbidden Planet, The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Incredible Shrinking Man, The Time Machine, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, THX-1138, Dark Star. On and on into the wee hours. Alas, I must admit that one highlight for me was the film Once, solely because the actress Marta Kristen, whom I had known since I was six years old as the prim Judy in Lost in Space, appeared in it naked.

I was seventeen, and virginal (if not lovely), I craved a girlfriend, and I was filled with lustful thoughts. On Saturday night, Larry and I went to the masquerade (“cosplay” was yet another term that had not yet been invented). We didn’t know it, but sci-fi convention masquerades traditionally involved a fair amount of nudity. On the one hand, masquerades had led to more female fan interest and participation at conventions; on the other hand, female fans were dressing up in accordance with (mostly) male artists’ prurient fantasies, and male fans were flocking to the masquerades to drool over them, and not infrequently harrass them. I will continue to not lie to you: the costumed person I most vividly remember was a young woman naked except for green and blue body paint from the waist up. I had no idea what character she was embodying, and I didn’t care. She looked like she was having a good time—I hope she was—and I’m glad she knew nothing of my geeky, drooly thoughts.

As the masquerade judges retired to deliberate, it was announced that all of us, while we awaited the results, would be entertained by a woman doing a strip tease. The thoughtless sexism of this I remember noticing. But I wonder whether I would have, if I hadn’t witnessed the reactions of the three or four women seated in my vicinity. They looked at each other in disbelief. One of them stood up to see better, to verify that this was indeed happening (we were far back on the flat floor of the ballroom), and my second most vivid recollection of the evening—after the half-naked woman I drooled over—was the sight of this member’s face as her disbelief turned to dismay, then anger. She looked as though the masquerade, and maybe the entire convention, had just been ruined for her.

Meanwhile, up on the makeshift stage that we could barely see, the strip tease continued, to the accompaniment of Joan Baez singing “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” Heinlein was sitting front and center, and when the performer removed her bra, she tossed it at him. Heinlein caught it and put it around his neck, the two cups laid along his shoulders to resemble epaulets. He stood at attention like an erect penis, and voilà, the cover of the program book had been recreated in tableau.

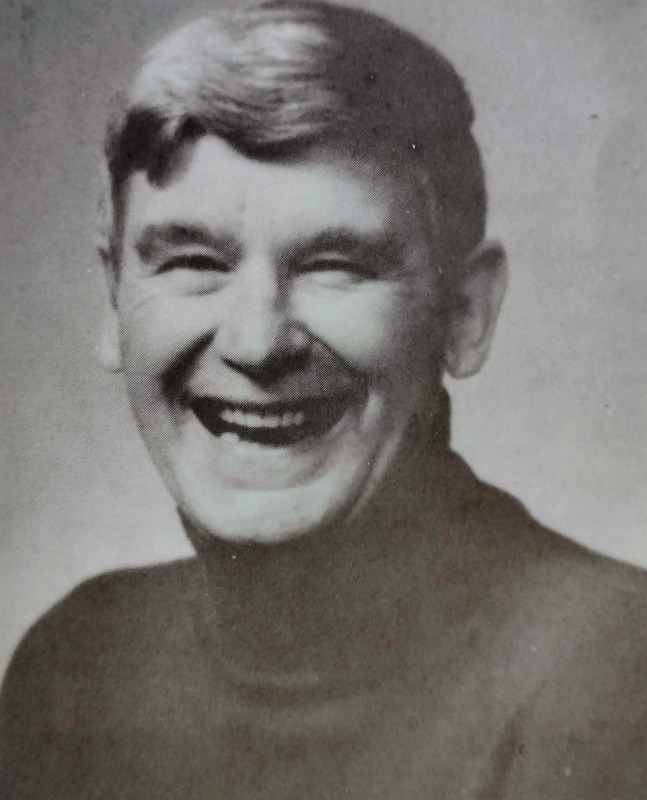

The following night was the Hugo Awards ceremony in the Municipal Auditorium. The Master of Ceremonies, a midwestern fan and writer named Bob Tucker, wore a geeky pink tuxedo with enormous lapels outlined in cherry—a foretaste of the clown costumes my friends and I would wear to next year’s senior prom, if we were lucky enough to have a girl ask us. (Most of our gay classmates wouldn’t come out to us until the 10th reunion.) Here’s Tucker’s photo in the program book:

Standing on a stage empty except for a podium with a microphone, he would announce the category—best editor, short story, novella, novel, etc—and its nominees, after which an unnamed silent woman would bring out a slip of paper identifying the winner. Tucker kept coyly playing with this woman, making come-hither gestures, demanding a kiss, pretending she was a dangerous wild animal. A certain portion of the audience—I’m guessing around 17%—finally hissed at this behavior, to which Tucker responded, “Are you hissing me? Just because of the lovely lady that I can kiss and you can’t?” (The quote is exact, because I recently watched a video recording of the proceedings to check my memory.) As each winner was announced, another unnamed silent woman would bring out the trophy, hand it over, and stand behind Tucker with her eyes cast down. All the winners were men, which wasn’t too surprising, since only three of the fifty-seven nominees were women. (Historical note: the first unnamed silent woman was Pat Cadigan, who later published a number of science fiction novels and short stories, including the Hugo-award winning novelette, “The Girl-Thing Who Went Out for Sushi.”)

The winner of Best Dramatic Presentation was the film, A Boy and His Dog. (That program cover again!) I had already seen it, and I had previously read the short story by Harlan Ellison on which it was based. In both versions, a boy and his telepathic pooch share a scrappy, anti-sentimental (read: drippingly sentimental) bromance in a violent post-apocalyptic America. A girl shows up from one of the “downunders,” scattered underground enclaves of staight-laced religious “squares,” and is introduced to fabulous sex by our lad. Of course she becomes avid for it, which is totally great—it’s also lucky for her that the boy can perform twenty times in a night—but unfortunately she’s also kind of pouty and spoiled and selfish and useless and conniving, so the happy ending is, when the dog is hungry and other food isn’t available, the boy kills her and feeds her to the dog. The movie version adds a jokey final line, when the dog opines that the girl had good judgment, “if not particularly good taste.” Ellison called this a “moronic, hateful, chauvinist last line, which I despise.” Noted.

All I’ll say about Heinlein’s guest of honor speech, following the awards ceremony, is that he glorified war and the strong men who fight it, and implied that “the primary function of what otherwise is a genetically spoiled female” is to produce babies to replace fallen heroes. Toastmaster Tucker ended the proceedings by confiding into the microphone, “When I told the Kansas City Committee that I would accept this job, they asked me what my fee was,” then raised a sly finger, turned and grabbed the nameless woman (this would be Pat Cadigan, not the other nameless woman who has remained nameless) and folded her back into a long smooch, while 72% of the audience erupted into wolf calls, whistles, and cheers.

To preserve my unbroken record of not lying to you—I doubt I would have noticed any of this, if I hadn’t witnessed, the previous evening, that other nameless woman’s outrage.

At the end of the convention, Larry and I parted. He headed back to D.C., while I boarded a bus to San Diego to visit another friend from music camp. I had bought a shopping bag full of sci-fi paperbacks, and on that 46-hour bus ride I read eight or ten of them. Because I was seventeen, and filled with lustful thoughts, I can recall only two things from those hundreds of pages. In Charles Platt’s Garbage World, the two main characters have sex in a mud puddle, which I liked. And in Heinlein’s Time Enough for Love, the extremely old hero who shares all of Heinlein’s political opinions has lots of sex with beautiful young women who are given to grateful utterances such as (I paraphrase), “I’m tired of sleeping with young pups who don’t know how to please a gal! Give me a man with experience!” This, I didn’t like. Was that merely because I was a young pup who knew even less than Heinlein’s pups? Or was there a tiny bit of hope for me?

Evidence for hope: one of the films screened at MidAmeriCon had had a brief and disastrous theatrical release in 1975, after which it was forgotten outside of midnight showings at the Waverly Theater in New York City. The Rocky Horror Picture Show appeared last on Saturday night’s program, at around 2am. Virginal, suburban, hetero, and normative, I had never imagined anything like Tim Curry’s Frank N. Furter, but my response to him, from the moment I laid eyes on him, was ecstatic. And judging from the ovation at the end by the mostly-male crowd—it’s the only event I’ve ever been present at where people really did “leap to their feet”—maybe a lot of us, stuffed with male privilege though we were, glimpsed the possibility that we were living in a cage, too.

Although I am about a decade younger than you are, and I have never attended a “con” of any kind, I could certainly see my teenage self (and my horrifying teenage reading list) in this piece (and its companion, “Enough.” I had the edition with the second cover art—the nude redheads cover). Although I was a big fan of Ursula LeGuin, Patricia McKillip, and Anne McCaffrey (just the dragon books though), I fell hard for Heinlein, and didn’t even begin to clue in to what a fascist pervert creep he was (and I use none of those words lightly) until I was at least seventeen, and I was even older before I finally repudiated him entirely.

Even now, I am leary of any environment likely to be dominated by “fans” of the things that I like. Even Beatles fans, who (I feel sure) are a pretty benign bunch. That sensation you described so well of seeing one’s fellow fans and instinctively going “ewww” has always stayed with me. But there is no denying that a big part of the draw (in all but a few classics of the genre—such as the early Dune novels) was the prospect of either sexy content, or a sexy girl or woman on the cover. Somewhere I think I still have a paperback copy of SECOND FOUNDATION where Arkady Darrell, the 12 or 13 year-old heroine of the second story in the book, has legs that went on for days. The story itself was about as sexy… well, about as sexy as Isaac Asimov himself.

Anyway, I always enjoy reading your stuff. Thanks for posting this.