Back when I and my two siblings were small enough to share a bathtub, our parents bought each of us a dinosaur-shaped bar of soap. I got a Brontosaurus, my older brother got a Tyrannosaurus rex, and my younger sister got a Triceratops. There was probably nothing random about this. My parents considered my older brother aggressive, my younger sister defensive, and me placid. My visual memory of that slate-blue bar of soap is still vivid. As I used it (sparingly, to preserve it as long as I could) the pleasing round smoothness of the neck, tail and legs just kept getting rounder and smoother and more pleasing.

Had I already loved and identified with Brontosaurus? It wouldn’t surprise me if my attachment began right then, as I placidly accepted the designation my parents assigned me. But then again, loads of kids love Brontosaurus; way more than Diplodocus or Apatosaurus, who look basically the same. I assume it’s because the meaning of Brontosaurus, which books always mentioned—“Thunder Lizard”—is way cooler than “Deceptive Lizard” (Apatosaurus) or “Double-Beamed” (Diplodocus), which has something to do with the shape of the tail vertebrae, but really, who could care.

Thunder Lizard! Gentle herbivore with the powerful name! Heraldic shield for shy, intimidated kids everywhere.

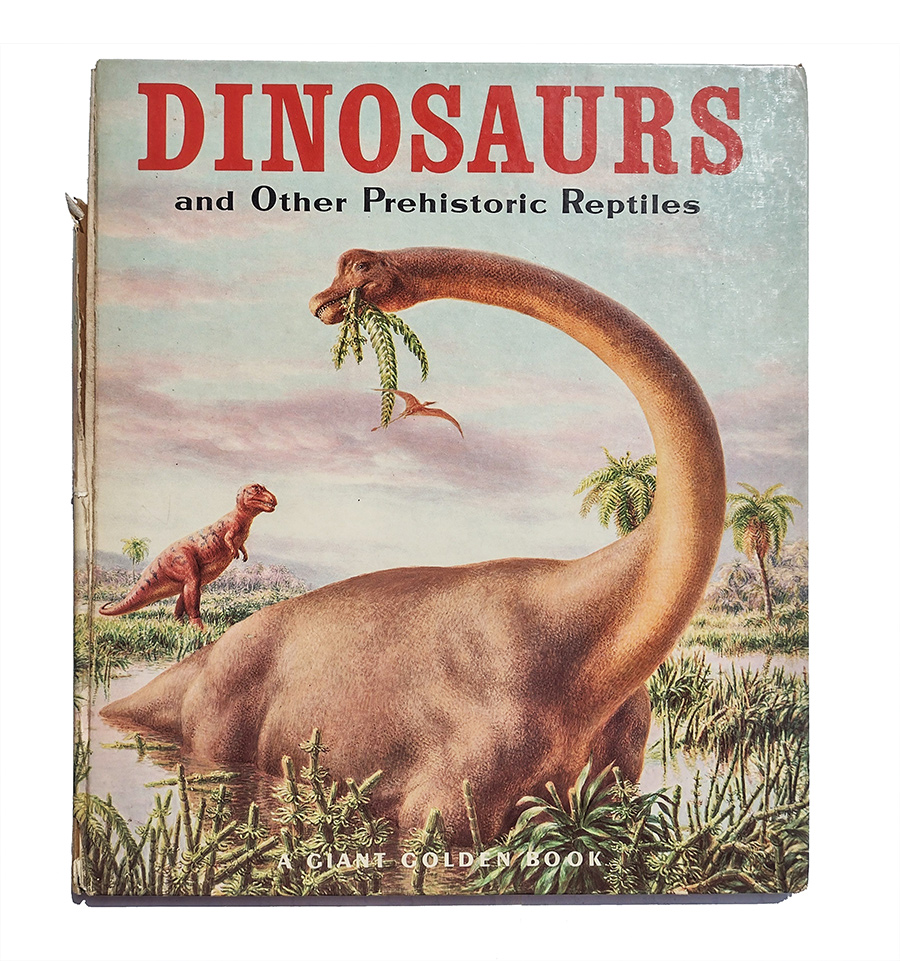

When I was six, my parents bought The Giant Golden Book of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Reptiles. I still have it; here’s the cover:

That creature chewing ferns is Brachiosaurus (“Arm Lizard,” for chrissake). Why, I wondered, would the Golden Book people choose this clown with the weird bony ridge on its head, when Bronto would have served just as well?

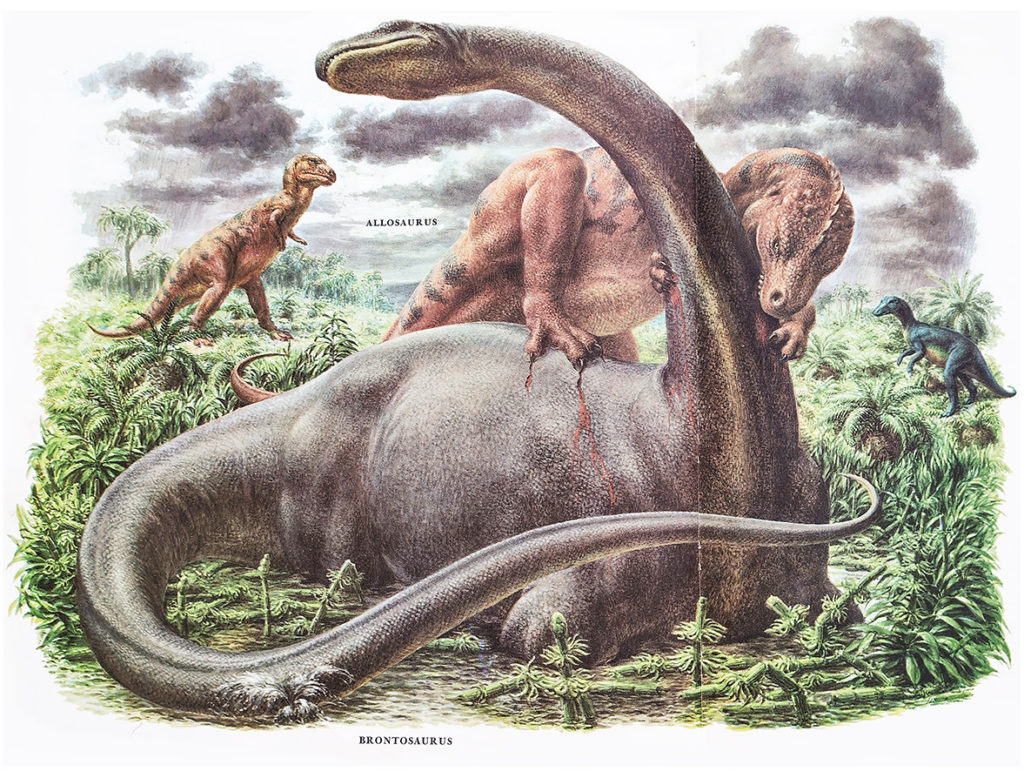

The book is sixty pages long, picturing dozens of dinosaur species, but it was the illustration of Brontosaurus that haunted me. It’s one of only two in the book depicting mayhem. I described it in my novel, The Stone Loves the World, but couldn’t reproduce it there. Here it is:

The accompanying text describes the attacking Allosaurus as male, the suffering Brontosaurus as female. Did I see myself in the Bronto, suffering at the hands of a schoolyard bully? Or was I beginning to have useless chivalrous thoughts—useless because I was a wimp and a coward—about saving bullied girls? I can’t remember. Looking at the illustration now, I admire the balanced arrangement of forms. All I saw then was that long and terribly vulnerable neck, the mean bite, the guiltless blood running down.