My mother never liked television, preferring to read mystery novels in her spare time. When, at the age of 77, she began to suffer dementia, she kept track of a book’s characters by writing their names on sticky tabs and affixing them to the pages on which they appeared. Her paperbacks bristled with scores of these brave little yellow flags. Then she surrendered, and started watching TV.

When I drove to Massachusetts on weekends to pay her bills, scout out needed repairs, and consult with her day-time aides, I would spend part of every day sitting on the couch with her in front of the tube. She still couldn’t stand broadcast or cable, she wanted to see only a handful of movies and series that she owned on DVD: Miracle of the White Stallions, National Velvet, a boxed set of three TV movies based on Dick Francis mysteries, The New Adventures of Black Beauty, The Saddle Club, and several equestrian documentaries. I saw all of these movies, episodes, and specials many times. Now and then, hoping for a little variety, I would suggest Babe, which I had bought for her, but she rarely agreed—the part of the horse in that movie was too small.

She was born Peggy Wood Smith, in 1929, and grew up in Friendship Heights, Washington, DC. She was an only child, and lonely. She fiercely resented her mother’s refusal to supply her with a sibling. She and her mother fought often, while her father remained unengaged and ineffectual. As my mother put it years later, “I hated my mother, but I despised my father, because he never stood up for me.” Here’s a studio portrait taken when she was five years old:

The child is mother of the woman—here’s her engagement photograph at twenty-two:

All her life, whenever she looked into a camera lens, her face took on this wary, challenging expression. It’s easy to imagine the caption, “Who the fuck are you?” She herself said, ruefully, that she always looked like the Bitch of Buchenwald. In casual photographs from her childhood, the only times she looks happy is when she’s holding an animal: a kitten, a dog, a chicken. She begged for a pet, and finally got one when she was seven, an energetic little fox terrier she named Stubby. Now she had a good reason not to look at the camera:

Stubby saved her life, so he deserves a hero shot:

(All the photos of Stubby are motion-blurred.)

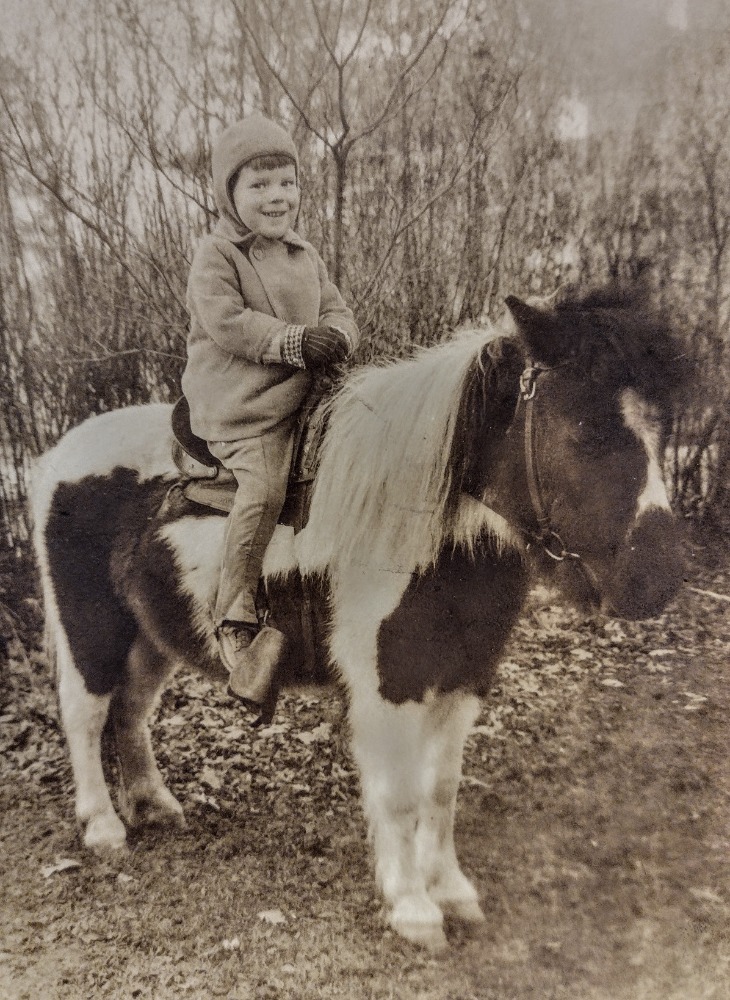

Since my mother didn’t start horseback riding until later, I used to think that Stubby was her gateway drug, but after she died I found this photo in an attic box:

Of the many photographs of my mother in childhood—she hated having her photo taken, yet her mother kept on taking photos—this expression of gleeful avidity is unique.

At some point in early adolescence she wore her mother down and obtained permission to take riding lessons. By 1944, she was a member of the American Women’s Voluntary Services, which was running an equestrian chapter out of Meadowbrook Stables in Chevy Chase, Maryland. She and her teenage colleagues spent afternoons and weekends galloping horses up and down Rock Creek Park, the idea being that if DC were invaded by parachuting Krauts or Japs and communication lines were cut, these gallant girls would transport messages in their dusty leather panniers from downtown command centers to far-flung field operatives. Later in life, my mother called it a “wonderful boondoggle.” Here’s a picture of her in uniform at fifteen, ready to ride for her country:

Her high school nickname was Smitty. She graduated in the spring of 1946. Her senior yearbook photo caption reads, “Just crazy ‘bout horses . . . darling girl . . . lots of fun . . . loves to ride, dance, and hunt (on horseback, of course!) . . . doesn’t like boys to smoke pipes . . . oh, to own a horse farm.” Flippant yearbook capsule descriptions are rarely as insightful as this one, in which horses are ardently evoked three times, while the lone reference to male humans is negative.

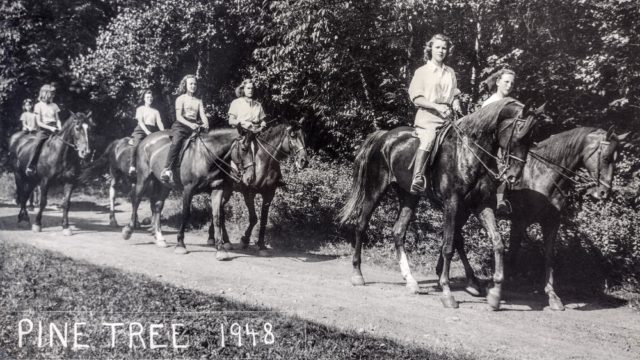

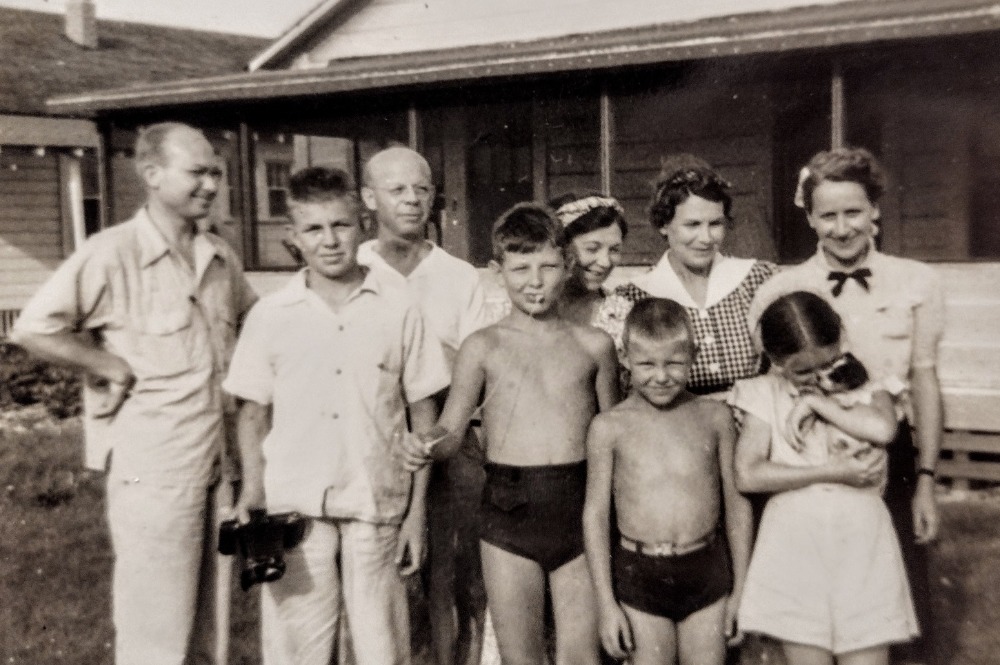

She entered Mount Holyoke College in the fall, and I verily believe that the next four years were the happiest of her life. Although she majored in chemistry, switching to physics in her senior year, she spent all of her spare time, and a fair amount of her study time, in the stable, on the trail, and in the ring. She and her fellow equestrians all had androgynous nicknames: there was already a Smitty, so she was Piglet. She spent little time at home with her parents during the summers; instead, she taught riding at Pine Tree, an all-girl camp in Pocono Pines. (That’s her, wondering who the fuck you are, in the top photo on the right.)

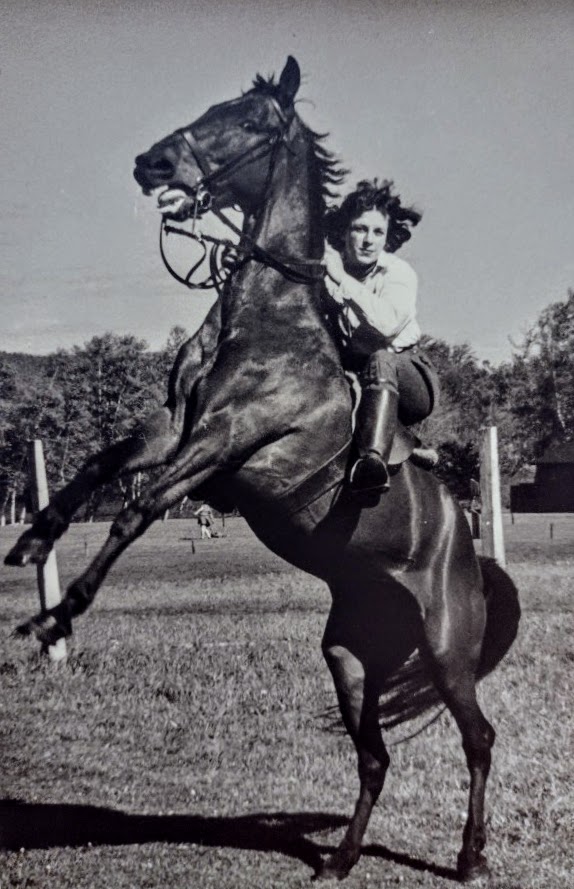

More than anything else, she loved competitive jumping on her favorite horse, College Flyer:

In this, she was the star student of Mount Holyoke’s Master of Equitation, George Nichols. He lived for jumping, too:

She graduated in 1950. Her commencement parade banner and class ring were decorated with that year’s symbol (Mount Holyoke rotates through four heraldic animals). I’ve always found it pleasing to contemplate—I know it’s hokey, it’s like a Dad joke, but I can’t help it—that this lonely and angry kid, this Peggy who found unalloyed happiness for the first and maybe the last time in her life soaring over jumps on a flying horse, graduated under the sign of Pegasus.

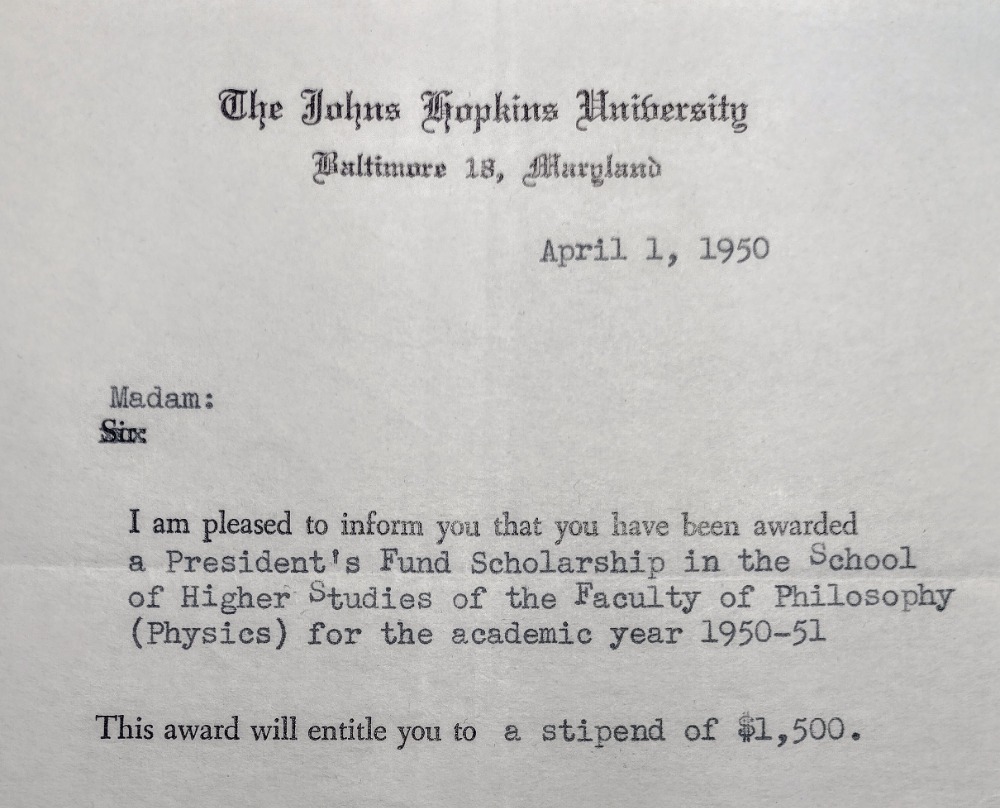

The last time? I’ve wondered. At some point during college she had begun to feel pain and numbness in her arms and hands, the first symptoms of a lifelong struggle with palindromic rheumatism. It was probably the reason she stopped serious riding, though she never said. She applied and was accepted into the graduate program in physics at Johns Hopkins University. She and my father always claimed she was the first woman ever to attend that program. I never got around to confirming this, but communications from the university suggest that female graduate students bordered on the inconceivable:

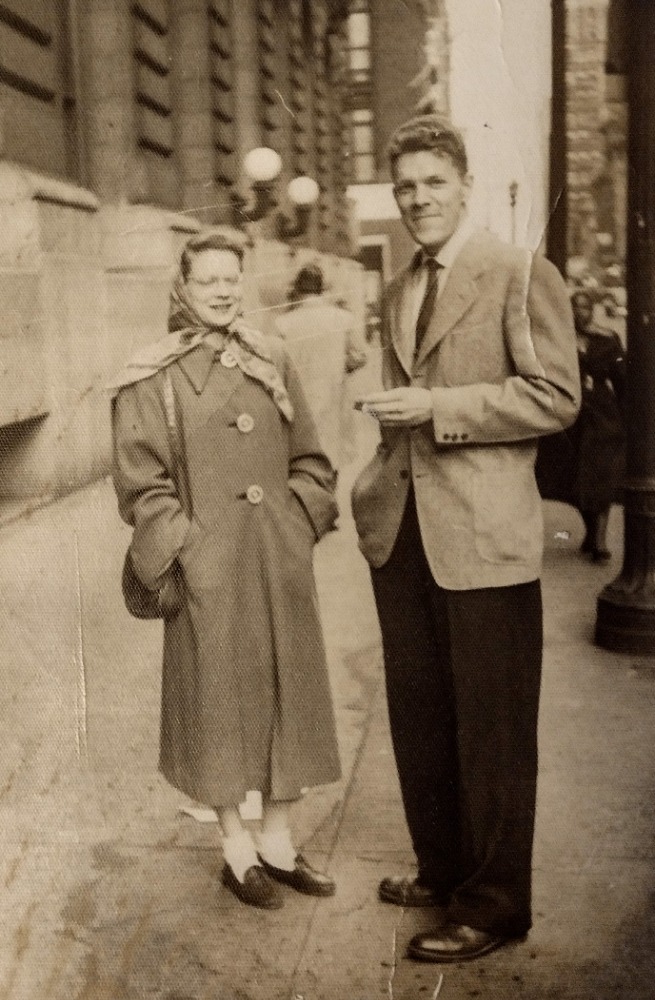

Maybe because she’d switched to physics only in her senior year, she struggled with her classes. A fellow grad student—whom she had already favorably picked out in the lecture hall because, she said years later, “he had the broadest shoulders”—helped her with her homework. By the middle of the spring semester, 1951, she had lost confidence, and in April she got engaged to the broad-shouldered man helping her, who was my father. In June she left the program and in December my parents married. The wedding photos were ruined because the photographer, my mother’s aunt, used a camera with a cracked housing. My mother never forgave her. But here’s the couple on a Baltimore street sometime during that year:

Gee, he does kind of have broad shoulders, doesn’t he?

My mother worked at a chemical company for five years while my father completed his PhD. Then he went on to his career, while my mother quit her job and got pregnant and became the person I knew growing up: a conscientious parent given to anxieties about her children and sudden frightening bursts of anger. She expressed love easily and often to the dogs in the house, less easily to her children, rarely and eventually never to my father. She cooked dinner every night, accepting little help—she would shoo everyone out of the kitchen—while assuring us that she hated cooking. She kept a clean house, and also kept on the wall a poster that read FUCK HOUSEWORK. On many days she hobbled around on aching ankles and knees, occasionally staying in bed when her entire ribcage attacked her. She chewed heroic amounts of aspirin—doctors were amazed at her failure to get an ulcer—and self-medicated with dry vermouth and gin-and-tonics. She retired alone to bed immediately after dinner, then popped out just as my father crawled in and spent the hours after midnight down in the blessed solitude and silence of the living room, reading a mystery and having another drink, her dogs dozing next to her.

When I was a teenager, my mother would occasionally announce to the room, “All men are assholes!” She made it sound like the title of an upcoming lecture. I might be standing there with my brother and my father, and we would look at each other, and my father would joke nervously, “Present company excluded, I hope?” My mother would jam her glasses up against the bridge of her nose and say nothing.

In my thirties and forties, I would have loved to ask her a few things, but I knew by then that I wouldn’t get anywhere. Had she only married my father because, in the 1950s, it was the only socially sanctioned way for a smart and proud woman to drop out of graduate school? Did her contempt for her father color her view of all men? Had she been so happy at Mount Holyoke partly because there weren’t any men around? And that bit about the broad shoulders—was there something equine in that? My father was tall, too—eighteen hands.

Regarding the last question: if a horse was the standard, my father would have disappointed her pretty fast. There was nothing gentle or biddable about him. He was smart, arrogant, and immovable in argument. When he thought you were being stupid, he made sure you knew it. The last twenty years of their marriage, with the children out of the house, were bleak. My mother moved into the bedroom that had once belonged to my brother and me. She filled the wall shelves and bookcases with murder mysteries and photos of her pets (all cats, now), on whom she showered love. There was only one photo of a human being, standing in a gold frame on her dresser:

I asked my mother who this person was, and she told me her name was Renate, that she had been a German pen pal many years ago. “Isn’t she beautiful?” my mother said, and I agreed she was. My mother had never mentioned Renate to me or my siblings. Later, when we moved her into a hospice for her last week, we set up photos of ourselves and of our late father, and also put this portrait on a lamp table near her bed.

After she died, I learned more from letters I found in the attic. While she was at Mount Holyoke, my mother, wanting in part to practice German, joined a group organized by a local church that was sending food aid to East Germans living under Russian domination in postwar poverty. Renate was a recipient of some of this aid, and she and my mother traded letters for several years. My mother didn’t copy her letters, so I only had Renate’s, which were long, affectionate and grateful. She urged my mother to visit her in East Germany once my father had completed his PhD. This new information fit with something I had known for a long time, because my mother had frequently recalled it with bitterness: when my father got his degree, my mother had earned enough money working at the chemical company to pay for a celebratory trip to Europe, but my father wanted to buy furniture instead. As I’ve already mentioned, my father never lost an argument.

Also in my mother’s attic were a number of enlarged professional photographs of her riding, jumping, and caring for horses at Mount Holyoke. There was one in particular that struck me:

My mother is the figure standing below. My brother now owns the original, and when I asked him to send me an electronic copy, he said something that matches my own feelings exactly: “I was looking at it recently, admiring Mom’s Katherine Hepburn-meets-Lauren Bacall poise and beauty, and thinking that I was looking at a wonderful life that Mom somehow did not manage to live out.”

The woman in the loft on the right was my mother’s best friend at college; her nickname was “Doc.” Here’s Doc in her glory:

My mother never attended any Mount Holyoke reunions. In 2000, for her class’s 50th, the reunion committee solicited from each alumna a page of news, which were bound into a presentation volume. This was another thing I discovered only after my mother had died. Out of the 262 still-living members of the class of 1950, 171 had submitted a page. My mother had not. I found Doc’s page, and learned that she had married in the same year as my mother, 1951. For forty years, she had bred and raised Connemara ponies; she was an inspector and board member of the American Connemara Pony Society; she had traveled extensively, was a birder, ran with Hash House Harriers; she took up sculpting when she was fifty, worked in Paris for four years, and became a member of the American Academy of Equine Art. She was the mother of five children.

I was reminded of that scene in Titanic, when the Leonardo DiCaprio character tells the Kate Winslet character that she must survive and “live a full life” (or something like that), and later we see the woman grown old, but busy at her pottery wheel, surrounded by photos of herself flying biplanes, climbing mountains, racing cars, and what not. (There are probably horses, too.) And if I instantly imagined Doc as the Kate Winslet character, that means I must have been imagining my mom as Leonardo, slipping off that too-small piece of flotsam and sinking into the darkness of the arctic water.

. . . oh, to own a horse farm.

When I cleared out the old house, one of the things I kept was my mother’s DVD of Miracle of the White Stallions. It’s a Walt Disney movie about the Lipizzaner horses of the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, who, toward the end of World War II, were threatened with destruction by Allied bombing, approaching armies, and the general chaos of a collapsing society. Of the various things my mother watched during her five years of increasing dementia, this was her favorite. I probably saw it sixty times. I never grew bored with it. Watching it felt like participating in a liturgy, and I used to play organ in a Congregational church, I used to sing Messiah every year, I like liturgy, I like the emotive power of extremely familiar words and gestures. After I’d seen the movie a dozen times, the ending—when the females of the precious Lipizzaner breed, trapped in the eastern zone of Europe at the close of the war, are rescued by General Patton from the encroaching Russian army, which would have eaten them—this ending, every time, brought tears to my eyes.

I loved reading this piece and seeing the wonderful photos of your mother, Brian. I feel sure I would have loved her, too. How sad that she spent so much of her adult life unhappy and in pain, but how it must have lifted her spirits to have you visit and watch movies with her!( I wonder if your mother knew my sister, a horse lover who was a student at Mt. Holyoke in 1951.)

I look forward eagerly to more of your posts!

Emily, what year did your sister graduate? And what was her name?

Brian, this is a wonderful, sad memoir of mom. ‘Preciate you quoting me on the hay barn photo. Interestingly, mom watched “Babe” with me almost every time I visited her. I always thought I was the black sheep of the family, but maybe I was also the cute pig in some way in mom’s mind.

Hi Brian,

I am just reading this again and it is really brilliant. In the photos where mom is near horses she is the most relaxed and looks rather movie-starish. I don’t she stood in that casual way in photos except when near a bar or horses.. Thanks again!!

This sketch (like that of the character apparently based on her in THE STONE) spoke powerfully to me, because I felt like I was reading a sketch of my mother-in-law’s life. Since everything in my life is about ten years behind yours, she was a small child during the war. Her parents were cold (and often drunk) but well-educated; when she was small she lived in Eastern Washington state where her father did something or other for the AEC. They did provide her with siblings—and how!—she was the oldest of six, but I think she has always preferred animals to people, and especially horses and cats. In the early to-mid sixties she took herself to Germany for six months to study biochemistry at Heidelburg as a part of seeking a doctorate in Bio-chem from Dartmouth. On her return she married my wife’s father, a history teacher at a boarding school with highly fictional sounding name of Cardigan Mountain. When, shortly after their first child (my wife) was born, he was offered an assistant head’s job in the suburbs of Boston, he took it, and that was it for her doctorate. For the next forty years she subordinated her much greater intelligence and education to the needs of his career. Adding insult to injury, at some point when their children nearly grown it became apparent that her husband was seeing men on the side—a fact that she decided to sit on for another twenty years, while she read—yes—mystery novels, rode her horse (she did manage, for a time to have the horse farm that she had dreamed of) and accumulated cats, all while seething in a stew of generalized misanthropy that it seemed like only other horse people were exempt from. Eventually, in about 2007, she reached her breaking point and separated from her husband—which upset him hardly at all—and forced herself to start all over in another state—not terribly successfully, and still filled with rage.

I find her story, and your mother’s, and those of many women of those two generations before the baby boom fascinating and (often) saddening. Thanks for indulging me here. The story seemed too similar not to share.